Who is the summary of Screenplay for?

This is the book summary of Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting. If you’re into screenwriting, this book is for you. It should actually be something like a bible for ya. Although Syd Field is pretty dead now his book lives on. Read it!

What is the summary of Screenplay?

Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting written by Syd Field is the second book about screenwriting coming up on this blog. And in my opinion it is the best one – at least if you´re a screenwriting newbie. Syd Fields book is very thorough and has a great structure that makes it easy to grasp the content. So if you´re only planning to read one book on screenwriting, this is the one.

One interesting thing that happens afterwards is that you start to watch films differently. You catch yourself analyzing, judging and improving the movie in our head while watching, and this is an amazing thing if you watch a lot of films – your mind is working in silence, contributing to you screenwriting knowledge base. Never underestimate your unconscious mind, that is where the biggest wisdoms are generated (read Kahneman´s Thinking Fast and Slow for more on that).

That is why I think it is nice to have the three books that I publish on this blog in your backpack – when you´re done with them your brain will help you take your knowledge further.

Facts about the summary of Screenplay

Book title: Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting

Book Author: Syd Field

Summary pages: 42

Year: 2005 (1982)

Genre: Screenwriting

Download summary of Screenplay

More about the summary of Screenplay

Read the summary of Screenplay

Chapter 1: Intro

What is a screenplay: The nature of the screenplay is the same as it has always been: A

screenplay is a story told with pictures, in dialogue and description, and placed within the context of dramatic structure. It is the art of visual storytelling.

Two aspects to deal with when writing a screenplay: When you want to write a screenplay, there are two aspects you have to deal with.

1. One is the preparation required to write it: the research, thinking time, character work, and

laying out of the structural dynamic.

2. The other is the execution, the actual writing of it, laying out the visual images and capturing

the dialogue. The hardest thing about writing is knowing what to write.

A good screenplay: When you read a good screenplay, you know it—it’s evident from page

one, word one. The style, the way the words are laid out on the page, the way the story is set up, the grasp of dramatic situation, the introduction of the main character, the basic premise or problem of the screenplay—it’s all set up in the first few pages of the script.

Chapter 2: What Is a Screenplay?

Screenplay vs. Novel: If you look at a novel and try to define its fundamental nature, you’ll

see that the dramatic action, the story line, usually takes place inside the head of the main character.

• We see the story line unfold through the eyes of the character, through his/her point of view.

We are privy to the character’s thoughts, feelings, emotions, words, actions, memories,

dreams, hopes, ambitions, opinions, and more.

• The character and reader go through the action together, sharing in the drama and emotion

of the story. We know how they act, feel, react, and figure things out. If other characters

appear and are brought into the narrative line of action, then the story embraces their point

of view, but the main thrust of the story line always returns to the main character. The main

character is who the story is about.

• In a novel the action takes place inside the character’s head, within the mindscape of dramatic

action. A play is different. The action, or story line, occurs onstage, under the proscenium

arch, and the audience becomes the fourth wall, eavesdropping on the lives of the characters,

what they think and feel and say. They talk about their hopes and dreams, past and future

plans, discuss their needs and desires, fears and conflicts.

• In this case, the action of the play occurs within the language of dramatic action; it is spoken

in words that describe feelings, actions, and emotions. A screenplay is different. Movies are

different. Film is a visual medium that dramatizes a basic story line; it deals in pictures, images,

bits and pieces of film.

Definition: We could say that a screenplay is a story told with pictures, in dialogue and

description, and placed within the context of dramatic structure.

A linear structure: Screenplays have a basic linear structure that creates the form of the

screenplay because it holds all the individual elements, or pieces, of the story line in place.

A holistic view: What is the relationship between the parts and the whole? How do you

separate one from the other? A story is the whole, and the elements that make up the story—the

action, characters, conflicts, scenes, sequences, dialogue, action, Acts I, II, and III, incidents, episodes, events, music, locations, etc.—are the parts, and this relationship between the parts and the whole make up the story.

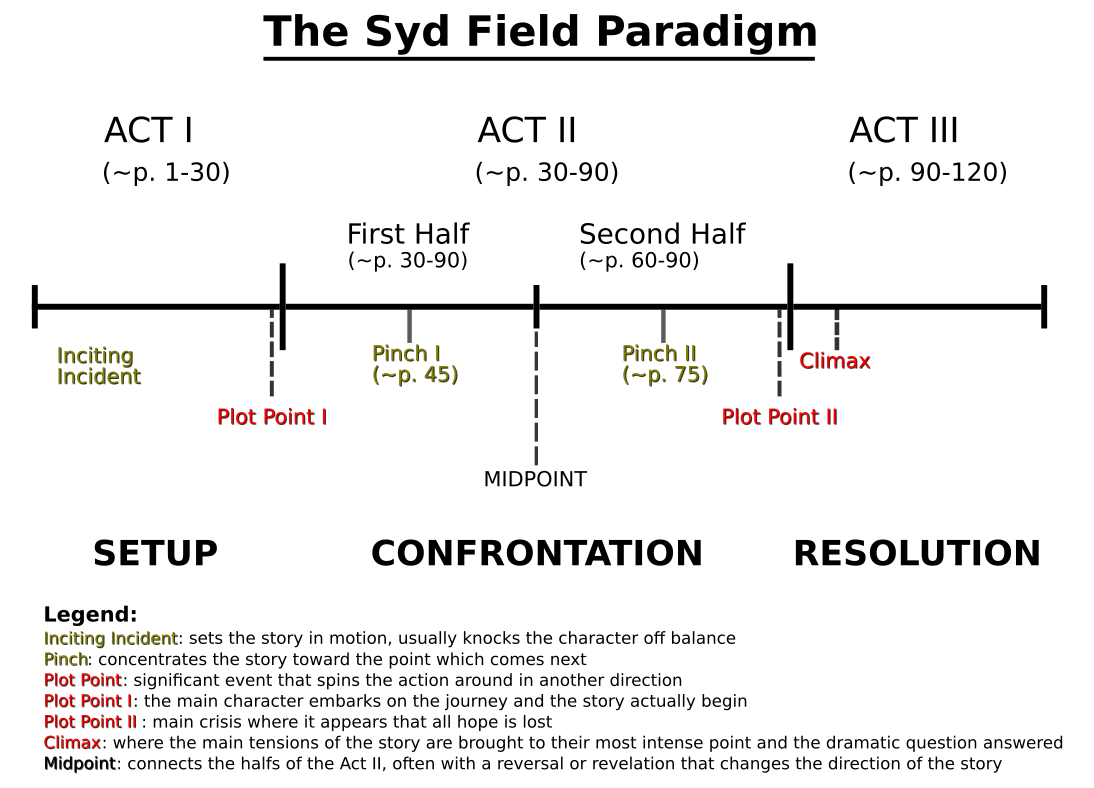

The three acts

ACT I IS THE SET-UP

One page of screenplay is approximately one minute of screen time. Act I, the beginning, is a unit of dramatic action that is approximately twenty or thirty pages long and is held together with the dramatic context known as the Set- Up. Context is the space that holds something in place – in this case, the content.

In this unit of dramatic action, Act I, the screenwriter sets up the story, establishes character, launches the dramatic premise (what the story is about), illustrates the situation (the circumstances surrounding the action), and creates the relationships between the main character and the other characters who inhabit the landscape of his or her world.

As a writer you’ve only got about ten minutes to establish this, because the audience members can usually determine, either consciously or unconsciously, whether they do or don’t like the movie by that time. The first ten-page unit of dramatic action is the most important part of the screenplay.

ACT II IS CONFRONTATION

Act II is a unit of dramatic action approximately sixty pages long, and goes from the end of Act I,

anywhere from pages 20 to 30, to the end of Act II, approximately pages 85 to 90, and is held together with the dramatic context known as Confrontation.

During this second act the main character encounters obstacle after obstacle that keeps him/her from achieving his/her dramatic need, which is defined as what the character wants to win, gain, get, or achieve during the course of the screenplay. If you know your character’s dramatic need, you can create obstacles to it and then your story becomes your character, overcoming obstacle after obstacle to achieve his/her dramatic need.

Act II is where your character has to deal with surviving the obstacles that you put in front of him or her. What is it that drives him or her forward through the action? What does your main character want? What is his or her dramatic need?

All drama is conflict. Without conflict, you have no action; without action, you have no character; without character, you have no story; and without story, you have no screenplay.

ACT III IS RESOLUTION

Act III is a unit of dramatic action approximately twenty to thirty pages long and goes from the end of Act II, approximately pages 85 to 90, to the end of the screenplay. It is held together with the dramatic context known as Resolution. I think it’s important to remember that resolution does not mean ending; resolution means solution.

Act III is that unit of action that resolves the story. It is not the ending; the ending is that specific scene or shot or sequence that ends the script. Beginning, middle, and end; Act I, Act II, Act III; Set-Up, Confrontation, Resolution—these parts make up the whole. It is the relationship between these parts that determines the whole.

Plot Point

• A Plot Point is defined as any incident, episode, or event that hooks into the action and spins

it around in another direction.

• Plot Point I occurs at the end of Act I, anywhere from pages 20 to 25 or 30. A Plot Point is

always a function of the main character.

• Plot Points serve an essential purpose in the screenplay; they are a major story progression

and keep the story line anchored in place.

• Plot Points do not have to be big, dynamic scenes or sequences; they can be quiet scenes in

which a decision is made.

• Plot Point II is really the same as Plot Point I; it is the way to move the story forward, from Act

II to Act III. It is a story progression. As mentioned, it usually occurs anywhere between pages

80 or 90 of the screenplay.

The dramatic structure of the screenplay may be denned as a linear arrangement

of related incidents, episodes, or events leading to a dramatic resolution. How you utilize these

structural components determines the form of your screenplay.

Read and study scripts like:

• Chinatown, Network (Paddy Chayefsky)

• American Beauty

• The Shawshank Redemption (Frank Darabont)

• Sideways (Alexander Payne and Jim Taylor)

• The Matrix

• Annie Hall

• Lord of the Rings.

These scripts are excellent teaching aids.

Chapter 3: The Subject

You need a subject: You need more than just an idea to start writing a screenplay. You

need a subject to embody and dramatize the idea. A subject is defined as an action and a character. An action is what the story is about, and a character is who the story is about.

Every screenplay has a subject—it is what the story is about. If we remember that a screenplay is like a noun, about a person in a place, doing his/her “thing,” we can see that the person is the main character and doing his/her “thing” is the action.

So, when we talk about the subject of a screenplay, we’re talking about an action and a character or characters. Every screenplay dramatizes an action and a character. You, as the screenwriter, must know who your movie is about and what happens to him or her. It is a primary principle in writing, not only in screenplays but in all forms of writing.

Knowing your subject is the starting point of writing the screenplay.

Dramatic premise: It’s essential to isolate your generalized idea into a specific dramatic

premise. And that becomes the starting point of your screenplay.

Reducing the story line: It may take several pages of free-association writing about your

story before you can begin to grasp the essentials and reduce a complex story line to a simple sentence or two. Don’t worry about it. Just keep doing it, and you will be able to articulate your story idea clearly and concisely.

Creative decisions: Every creative decision must be made by choice, not necessity. If your

character walks out of a bank, that’s one story. If he runs out of a bank, that’s another story.

Your subject will find you, given the opportunity. It’s very simple. Trust yourself. Just

start looking for an action and a character. When you can express your idea succinctly in terms of action and character—my story is about this person, in this place, doing his/her ”thing”—you’re beginning the preparation of your screenplay.

Expressing the story clearly: When you can express your idea succinctly in terms of

action and character—my story is about this person, in this place, doing his/her ”thing”—you’re

beginning the preparation of your screenplay. The next step is expanding your subject. Fleshing out the action and focusing on the character broadens the story line and accentuates the details. Gather your material any way you can. It will always be to your advantage.

Research: By doing research you acquire information. The information you collect allows you to operate from the position of choice, confidence, and responsibility. You can choose to use some, or all, or none of the material you’ve gathered; that’s your choice, dictated by the terms of the story. Not using it because you don’t have it offers you no choice at all, and will always work against you and your story.

The principle rule of storytelling: The more you know, the more you can communicate.

The character’s need determines the creative choices he/she makes during the

screenplay, and gaining clarity about that need allows you to be more complex, more dimensional, in your character portrayal.

The key to a successful screenplay, Waldo emphasized, was preparing the material. Dialogue, he said, is “perishable,” because the actor can always improvise lines to make

something work. But, he added forcefully, the character’s dramatic need is sacrosanct. That cannot be changed, because it holds the entire story in place. Putting words down on paper, he said, is the easiest part of the screenwriting process; it is the visual conception of the story that takes so long.

There are two kinds of action – physical action and emotional action. Physical action

can be a battle sequence. Emotional action is what happens inside your characters during the story.

Ask yourself what kind of story you are writing. Is it an outdoor action adventure movie, or is it a story about a relationship, an emotional story? Once you determine what kind of action you’re dealing with, you can move into the life of your character. First, define the dramatic need of your character. What does your character want? What is his/her need? What drives

him to the resolution of your story?

The primary ingredients: Conflict, struggle, overcoming obstacles, both inside and outside, are the primary ingredients in all drama—in comedy, too. It is the writer’s responsibility to

generate enough conflict to keep the reader, or the audience, interested. The job of the screenwriter is to keep the reader turning pages. The story always has to move forward, toward its resolution. And it all comes down to knowing your subject.

Without action, there is no character. Action is Character. What a person does is what he is, not what he says.

Chapter 4: The Creation of Character

Events in a screenplay are specifically designed to bring out the truth about the characters so that we, the reader and audience, can transcend our ordinary lives and achieve a connection, or bond, between “them and us.” We see ourselves in them and enjoy a moment, perhaps, of recognition and understanding.

Incidents: Henry James says that the incidents you create for your characters are the best ways

to illuminate who they are—that is, reveal their true nature, their essential character. How they

respond to a particular incident or event, how they act and react, what they say and do is what really defines the essence of their character.

Film is behavior. Because we’re telling a story in pictures, we must show how the character

acts and reacts to the events that he/she confronts and overcomes (or doesn’t overcome) during the story line.

Main character: You can have more than one main character, of course, but it certainly

clarifies things if you identify a single hero or heroine.

Character Creation Process

First, establish your main character. Who is your story about? Separate the components of his/her life into two basic categories: interior and exterior. The interior life of your character takes place from birth up until the time your story begins. It is a process that forms character.

The exterior life of your character takes place from the moment your film begins to the conclusion of the story. It is a process that reveals character. Film is a visual medium. You must find ways to reveal your character’s conflicts visually.

You cannot reveal what you don’t know. Thus, it’s important to make the distinction between knowing your character as a thought, notion, or idea in your head and revealing him or her on paper.

The Character Biography is an exercise that reveals your character’s interior life, the

emotional forces working on your character from birth. When you begin formulating your character from birth, you begin to see your character build. Pursue his/her life through the first ten years; include his/her preschool and school years, relationships with friends and family and teachers. Continue to trace your character’s life until the story begins.

Questions and answers: Writing is the ability to ask yourself questions and wait for the

answers. As a side note, it’s important to phrase your creative questions to begin with the word what, not why. Try to phrase any questions using the word what: What causes my character to react in this manner?

The interior life: You’re building the interior life of your character, the emotional life, on a

firm foundation so that your character can move and evolve in a definite character arc through the story, can change and grow through certain emotional stages of the action.

The exterior life: Once you’ve established the interior aspect of your character in a character

biography, you can move into the exterior portion of your story. The exterior aspect of your character takes place during the actual time of the screenplay, from the first fade-in to the final fade-out.

Three basic components: How do you make your characters real, believable, and multidimensional people during your story? From fade-in to fade-out? The best way to do this is to separate your characters’ lives into three basic components—their professional life, their personal life, and their private life.

1. Professional: What does your main character do for a living? The clearer you are, the more

believable your characters become. In a free-association essay of about a page or two, define

your character’s professional life. Don’t try to censor yourself; just throw it all down on the

page.

2. Personal: Is your main character married, single, widowed, divorced, or separated?

3. Private: What does your character do when he or she is alone?

Why three components: What’s so beneficial about knowing your characters’ professional, personal, and private lives is that you have something to cut away to; if you are writing your screenplay and don’t know what happens next, you can go into the professional, personal, or private aspects of your character’s life and find something to show to move the story forward.

Activity: Your character has to be active, has to be doing things, causing things to happen, not just reacting all the time.

Break your character’s life down into the first ten years, the second ten years, the

third ten years, and beyond. Write about five to seven pages in free association, and if you choose, write more.

Building a Character

Four essential qualities that seemed to go into the making of good characters:

1. The characters have a strong and defined dramatic need

2. They have an individual point of view

3. They personify an attitude

4. They go through some change, or transformation.

Those four elements, those four qualities, make up good character.

Dramatic need

Dramatic need is defined as what your main characters want to win, gain, get, or achieve during the course of your screenplay. The dramatic need is what drives your characters through the story line. It is their purpose, their mission, their motivation, driving them through the narrative action of the storyline.

EXAMPLE: In Thelma & Louise, the dramatic need is to escape safely to Mexico.

Point of view

The second thing that makes good character is point of view. Point of view is defined as the way a person sees, or views, the world. Every person has an individual point of view. Point of view is a belief system, and as we know, what we believe to be true is true.

Point of view is neither right nor wrong; it is as singular and distinctive as a rose on a rosebush. No two leaves, no two flowers, no two people are ever the same.

Your character’s point of view may be that the indiscriminate slaughtering of dolphins and whales is morally wrong because they are two of the most intelligent species on the planet, maybe smarter than man.

Your character supports that point of view by participating in demonstrations and wearing T-shirts with Save the Whales and Dolphins on it. Look for ways your characters can support and dramatize their points of view. Knowing your characters’ points of view becomes a good way to generate conflict.

Attitude

The third thing that makes good character is attitude. Attitude is defined as a manner or opinion, and is a way of acting or feeling that reveals a person’s personal opinion. An attitude, differentiated from a point of view, is an intellectual decision, so it can, and probably will, be classified by a judgment: right or wrong, good or bad, positive or negative, angry or happy, cynical or naive, superior or inferior, liberal or conservative, optimistic or pessimistic. Being ”right” all the time is an attitude; so is being “macho.”

Understanding your character’s attitude allows him/her to reach out and touch his/her humanity in an individual way.

Transformation

The fourth element that makes up good character is change, or transformation. Does your character change during the course of your screenplay? If so, what is the change? Can you define it? Articulate it? Can you trace the emotional arc of the character from the beginning to the end?

Having a character change during the course of the screenplay is not a requirement if it doesn’t fit your character.

Film is behavior: it’s important to remember that when you’re writing a screenplay, the main

character must be active; she must cause things to happen, not let things happen to her. Its okay if she reacts to incidents or events some of the time, but if she is always reacting, she becomes passive, weak, and that’s when the character seems to disappear off the page.

Minor characters appear more interesting than main character and seem to have more life and

flamboyance. Film is behavior; action is character and character, action; what a Person does is who he is, not what he says.

Let them do what they want: When you’re writing you’ll find it may take you about

sixty pages before you make contact with your characters, before they start talking to you, tell you what they want to do and say. Once you’ve made contact and established a connection with them, they’ll take over. Let them do what they want. Just don’t expect your characters to start talking to you from page one. It doesn’t work that way.

Writing dialogue is a learning process, an act of coordination. The more you do it, the easier

it gets. Dialogue serves two main purposes: Either it moves the story forward, or it reveals information about the main character. If the dialogue does not serve either one of these functions, then take it out.

It’s okay for the first sixty pages of your first draft to be filled with awkward dialogue.

The end result of all your work and research and preparation and thinking time will be characters who are authentic and believable, real people in real situations. And that’s what it’s all about.

Chapter 5: Story and Character

There are really only two ways to approach writing a screenplay. One is to get an idea, then create your characters to fit that idea.

Another way to approach a screenplay is by creating a character, then letting a need, an action, and, ultimately, a story emerge out of that character.

Chapter 6: Endings and beginnings

Remember that the definition of screenplay structure is “a linear progression of related incidents, episodes, and events leading to a dramatic resolution.” That means your story moves forward from beginning to end.

You’ve got approximately ten pages (about ten minutes) to establish three things to your reader or audience:

(1) Who is your main character?

(2) What is the dramatic premise—that is, what’s your story about?

(3) What is the dramatic situation—the circumstances surrounding your story?

The ending is the first thing you must know before you begin writing. Why? It’s obvious, when you think about it. Your story always moves forward—it follows a path, a direction, and a line of progression from beginning to end. Direction is defined as a line of development, the path along which something lies.

In the same way, everything is related in the screenplay, as it is in life. You don’t have to know the specific details of your ending when you sit down to write your screenplay, but you have to know what happens and how it affects the characters.

Resolution: Understanding the basic dynamics of a story’s resolution is essential. By itself,

resolution means “a solution or explanation.” And that process begins at the onset, at the very

beginning of the screenwriting process. When you are laying out your story line, building it, putting it together, scene by scene, act by act, you must first determine the resolution.

What is the solution of your story? At the moment of the initial conception of your screenplay, when you were still working out the idea and shaping it into a dramatic story line, you made a creative choice, a decision, and determined what the resolution was going to be.

The resolution must be clear in your mind before you write one word on paper; it is context, it holds the ending in place. Billy Wilder once remarked that if you ever have a problem with your ending, the answer always lies in the beginning. To write a strong opening, you must know your ending.

Thirty pages: As a reader, I give writers thirty pages to set up the story, and if it´s not done by

then I reach for the next script on the pile.

Ten pages: You’ve only got about ten pages to grab the attention of your reader or audience;

that’s why so many films open with an attention-grabbing sequence. The screenwriter’s job is to keep the reader turning pages. The first ten pages of your screenplay are absolutely the most crucial.

Inciting incident: Once you establish the inciting incident, you can set up the rest of your

story.

Before you write one shot, one word of dialogue on paper, you must know four things:

• Your ending

• Your beginning

• Plot Point I

• Plot Point II

In that order. These four elements, these four incidents, episodes, or events, are the cornerstones, the foundation, of your screenplay.

The opening of your script will determine whether the reader continues reading your

screenplay or not. He or she must know three things within these first few pages of the script:

• The character—who the story is about

• The dramatic (or comedy)

• Premise—what the story is about

• The situation—the circumstances surrounding the action.

Within those first ten pages, the reader is going to make a decision about whether he/she likes or dislikes the material.

Loose ends: It’s important to tie together all the loose ends of the narrative line so the

screenplay becomes a complete reading and visual experience (in the mind’s eye) that rings true and is integral to the action and the characters.

So what makes a good ending? It has to work, first of all, by satisfying the story;

when we reach the final fade-out and walk away from the movie experience, we want to feel full and satisfied, much as if we were leaving the table after a good meal. It’s this feeling of satisfaction that must be fulfilled in order for an ending to work effectively. And, of course, it’s got to be believable.

The ending comes out of the beginning: If I could sum up the concept of

endings and state the one most important thing to remember, I would say: The ending comes out of the beginning. Someone, or something, initiates an action, and how that action is resolved becomes the story line of the film.

Chapter 7: Setting up the story

Everything is related. If we go back to the second definition of structure, it states that

there is a causal “relationship between the parts and the whole.” If you change a scene or a line of dialogue on page 10, it impacts and influences a scene or a line of dialogue on page 80.

A screenplay is a whole, and exists in direct relationship to its parts. Therefore, it becomes essential to introduce your story from the very beginning, from page one, word one.

Setup your story visually: Setting up your story by explaining things through dialogue

slows down the action and impedes the story progression. A screenplay is a story told with pictures, remember, so it’s important to set up your story visually.

Chapter 8: Two incidents

The definition of incident: “a specific event or occurrence that occurs in relation to

something else.”

The inciting incident serves two important and necessary functions in the craft of storytelling:

1. It sets the story in motion

2. It grabs the attention of the reader and audience.

Seeing the relationship between this first incident and the story line is essential to an understanding of good screenwriting.

Essence of tragedy: Hegel, the great eighteenth-century German philosopher, maintained

that the essence of tragedy derives not from one character being right and the other being wrong, or from the conflict of good versus evil, but from a conflict in which both characters are right, and thus the tragedy is one of “right against right,” being carried to its logical conclusion.

All drama is conflict: Without conflict you have no action; without action you have no

character; without character you have no story; and without story you have no screenplay.

The inciting incident

Depending on the kind of story you’re writing, the inciting incident will either be action-driven or character-driven. It does not have to be a tense action or dramatic sequence. The inciting incident always leads us to the key incident, which is the hub of the story line, the engine

that powers the story forward. The key incident reveals to us what the story is about.

Key incident

Many times the key incident and Plot Point I are the same. When you begin writing your screenplay, it’s essential that you know the distinctions between the inciting incident and the key incident.

The dramatic premise could be said to be a conceptual description of what the story is about, while the key incident would be that specific scene or sequence that is the dramatic visualization of what the story is about.

Act I is a unit of dramatic action that is approximately twenty or thirty pages long;

it begins at the beginning of the screenplay and goes to the Plot Point at the end of Act I. It is held together with the dramatic context known as the setup. If you recall, context is the empty space that holds the content in place.

This unit of dramatic action sets up your story; it sets up the situation and the relationships between the characters, and establishes the necessary information so the reader knows what’s happening and the story can unfold clearly. The first ten pages of your screenplay, as mentioned, establish three specific things. The main character is introduced so we know who the story is about.

Dramatic premise

The second thing we create within this first ten-page unit of action is the dramatic premise. What is this story about? We can state it through dialogue, as in Chinatown, or show it visually, through the inciting incident, as in Crimson Tide.

The third thing we need to establish is the situation, the circumstances surrounding the action, as in Mystic River, or Finding Neverland, or Sideways. The two incidents provide the foundation of the story line. The 138 inciting incident sets the story in motion and the key incident establishes the story; it is the dramatic premise executed.

Structure is not something embedded in concrete, or something that is unbending, or unyielding; rather, it is flexible, like a tree that bends in the wind but doesn’t break.

Understanding this concept allows you to play with the break. Understanding this concept allows you to play with the plotline so you can tell your stories visually, with narrative action rather than explanation.

Chapter 9: Plot points

James Joyce, the great Irish novelist, once remarked that the experience of writing is like

climbing a mountain: When you’re in the middle of your climb, you can only see what’s directly in front of you and what’s directly above you. You can plan only one move at a time.

You can’t see two or three moves above you or how you’re going to get there. Only when you reach the top of the mountain can you look down and gain some kind of an overview of the landscape you’ve negotiated.

As defined, the Plot Point is “any incident, episode, or event that hooks into the action

and spins it around in another direction.”

There are many Plot Points scattered throughout the screenplay, but when you’re confronting 120 blank sheets of paper, you need to know only four things to structure your story line: the ending, the beginning, and Plot Points I and II.

The function of the Plot Point is simple: It moves the story forward. Plot Point I and Plot Point II are the story points that hold the paradigm in place. They are the anchors of your story line.

The purpose of the Plot Point is to move the story forward: the importance of the four things you need to know before you put one word down on paper: the ending, beginning, and Plot Points I and II. If you don’t know those four points, you’re in trouble. This does not mean that there are only two Plot Points in your screenplay.

That’s not the case at all. We’re dealing with the preparation you need to make before you begin

writing. Once you know what these two Plot Points are, they will anchor your story line, hold it in place so you can begin the writing process with freedom and creativity.

When the screenplay is completed, it may contain as many as ten to fifteen Plot Points, most of which will be in Act II. How many you have, again, depends upon your story. The purpose of the Plot Point is to move the story forward, toward the resolution. That is its purpose.

Plot points exercise

• See if you can locate the Plot Points at the end of Act I and Act II. Every film you see will have

definite Plot Points; all you have to do is find them. If you want, take a look at your watch

anywhere from twenty to thirty minutes into the film (depending on its length, of course) and

see if you can determine what the action point is; ask yourself what’s happening, or what’s

going on in the story around this point in the action.

• There will be some kind of incident, episode, or event that will occur. Discover what it is, and

when it occurs. Do the same for Act II. Around eighty or ninety minutes into the feature, check

out what’s happening in the story line.

• What incident, episode, or event occurs that will lead us into Act III, the Resolution7. What

happens around this time in the movie? It’s an excellent exercise. The more you do it, the

easier it gets. Pretty soon it will be ingrained in your consciousness; you’ll grasp the essential

nature of the relationship between structure and story.

• Then you’ll see how the definition of dramatic structure—”a series of related incidents,

episodes, and events leading to a dramatic resolution”— guides you through the story line.

Plot Points are those incidents, episodes, and events that anchor your story line; they provide

the foundation of the narrative line of action.

A Plot Point does not have to be a dramatic moment, or a major scene or sequence. A Plot Point can be a quiet moment, as in Plot Point II in Thelma & Louise, or an exciting action sequence, as in Plot Point I in Collateral, or a line of dialogue, as in The Matrix, or a decision that affects the story line, as in Chinatown.

A Plot Point is whatever you choose it to be—it could be a long scene or a short one, a moment of

silence or of action; it simply depends on the script you’re writing. It’s the choice of the screenwriter, but it is always an incident, episode, or event that is dictated by the needs of the story.

The anchoring pins of dramatic action: Knowledge and mastery of the Plot Point is an essential requirement of writing a screenplay. As you approach the 120 blank sheets of paper, the Plot Points at the end of each act are the anchoring pins of dramatic action; they hold

everything together. They are the signposts, the goals, the objectives, the destination points of each act—forged links in the chain of dramatic action.

Chapter 10: The scene

“A hero is someone who has given his or her life to something bigger than oneself”

Good scenes make good movies. When you think of a good movie, you remember

scenes, not the entire film.

The scene is the single most important element in your screenplay. It is where something happens—where something specific happens. It is a particular unit, or cell, of dramatic (or comédie) action—the place in which you tell your story.

The purpose of the scene is twofold: Either it moves the story forward or it

reveals information about the character. If the scene does not satisfy one, or both, of these two

elements, then it doesn’t belong in the screenplay.

It is the story that determines how long or how short your scene is. There is only

one rule to follow: Tell your story. The scenes will be as long or as short as they need to be; just trust the story and it will tell you everything you need to know.

Place and time

Two things are necessary in every scene— place and time. They are the two components that hold things in context. Every scene occurs at a specific place and at a specific time.

Time: What time of the day or night does your scene take place? In the morning? Afternoon? Late at night? All you have to do is specify either day or night. But sometimes you may want to be more specific: sunrise, early morning, late morning, midafternoon, sunset, or dusk. All you need to indicate is DAY or NIGHT.

If you change either place or time, it becomes a new scene. Why? Because each time you change one of these elements, you have to change the lighting of the scene and, almost always, the camera placement.

Place: If your scene takes place in a house, and you move from the bedroom to the kitchen to the living room, you have three individual scenes.

Scene construction: A scene can be constructed in several different ways, depending on

the type of story you’re telling. For many types of scenes you can build the action in terms of beginning, middle, and end; a character enters the place—restaurant, school, home—and the scene unfolds in linear time, much the way a screenplay unfolds.

Or you can begin a scene, cut away to a flashback, as in The Bourne Supremacy or Ordinary People, then bring it back to the present and end it in real time.

Reveal: Every scene must reveal one element of necessary story information to the reader or

audience; remember, the purpose of the scene is to either move the story forward or to reveal

information about the character. Rarely does a scene provide more than one piece of information.

There are two kinds of scenes. One is where something happens visually, the other

is a dialogue scene between two or more characters. Most scenes are a combination.

Dialogue length: most dialogue scenes need be no longer than two or three pages.

Your story always moves forward: Within the body of the scene, something specific happens— your characters move from point A to point B in terms of emotional growth or

reaching a decision; or your story links point A to point B in terms of the narrative line of action, the plot. Your story always moves forward, even if parts of it are told in flashback.

The flashback is a technique used to expand the audience’s comprehension of story, characters, and situation. The purpose of the flashback is the same as the scene—either it moves the story forward or it reveals information about the characters.

Creating a scene

How do you go about creating a scene? First create the context of the scene, then determine the

content, what happens.

• What is the purpose of the scene?

• Why is it there? How does it move the story forward?

• What happens within the body of the scene?

• Where has the character just been before he enters the scene? What are the emotional forces

working on the character during the scene?

• Do they impact the purpose of the scene?

• What is his/her purpose in the scene?

• Why is he/she there? To move the story forward or to reveal information about the character?

By creating context, you determine dramatic purpose and can build your scene line by line, action by action. By creating context, you establish content. How do you do this? By finding the components or elements within the scene. What aspect of your character’s professional life, personal life, or private life is going to be revealed?

Against the grain: When you’re approaching a scene, look for a way that dramatizes the

scene “against the grain” or a location that could make it visually interesting.

When you’re preparing to write a scene:

1. First establish the purpose

2. Then find the components, the elements contained within the scene

3. Then determine the content

Within the context of the scene you can influence tone, feeling, and mood by the descriptions you write.

In comedy, you can’t have your characters playing for laughs; they have to believe what they’re

doing, otherwise it becomes forced and contrived, and therefore unfunny. In comedy, Woody Allen says, “Acting funny is the worst thing you can do.”

Comedy, like drama, depends on “real people in real situations.” When you set out to write a scene, find the purpose of the scene and root it in place and time. Then establish the context and determine the content, and find the elements or components within the scene to build it and MAKE IT WORK.

Chapter 11: The sequence

A screenplay is a system: The screenplay is comprised of a series of elements that can

be compared to a system, a number of individually related parts arranged to form a unity, or whole. A screenplay is really a system of sorts, comprised of specific parts that are related and unified by action, character, and dramatic premise. We measure it, or evaluate it, in terms of how well it works or doesn’t work.

The sequence is perhaps the most important element of the screenplay. A sequence is a series

of scenes connected by one single idea with a definite beginning, middle, and end. It is a unit, or block, of dramatic action unified by one single idea. It is the skeleton, or backbone, of your script.

A series of scenes connected by one single idea: A sequence is a series of scenes connected by one single idea, usually expressed in a word or two: a wedding, a funeral; a

chase; a race; an election; a reunion; an arrival or departure; a coronation; a bank holdup.

The context of the sequence is the specific idea that can be expressed in a few words

or less. The race between Seabiscuit and War Admiral, for example, is a unit, or block, of dramatic action; it is the context, the idea that holds the content in place.

The content of the sequence: Once we establish the context of the sequence, we

build it with content, the specific details, or ingredients, needed to create the sequence. The sequence is a key part of the screenplay because it holds essential parts of the narrative action in place, much like a strand holds a diamond necklace in place. You can literally string or hang a series of scenes together to create chunks of dramatic action.

A creative, limitless context: Sequences can be written any way you want; they are a

creative, limitless context within which to paint your picture against the canvas of action. It should be noted that there are no specific number of sequences in a screenplay; you don’t need exactly twelve, eighteen, or twenty sequences to make up your script. Your story will tell you how many sequences you need.

Action sequence: When you’re writing an action screenplay, like The Bourne Supremacy or

Collateral, the focus must be on action and character; the two must reside in and interact with each other. Writing an action sequence is a definite skill, and good action scripts are written with color, pacing, suspense, tension, and, in most cases, humor.

Sometimes, if a script does not seem to be working as well as it should, or you feel there’s a problem in terms of pacing, or things seem dull and boring, you might think about adding some kind of action sequence to keep the story moving and the tension taut. Sometimes you have to make some drastic creative choices to pump up the story line.

More ways to say that someone runs: The material has to be designed for and incorporated into your story line, then executed to the best of your ability. Often the easy way out—a car chase, or a kiss, or a shoot-out, or a murder attempt—draws attention to itself and therefore doesn’t work. The key to writing a good action sequence is finding more ways to say that someone “runs.”

Choreograph the action: So what’s the best way to write an action sequence? Design

it; choreograph the action from the beginning, through the middle, and on to the end. Choose your words carefully when you’re writing.

Action is not written with a lot of long and beautifully styled sentences. Writing an action sequence has got to be intense, visual. The reader must see the action as if he or she were seeing it on the screen.

But if you write too little, and don’t flesh out the action as much as you should, the action line becomes thin and doesn’t carry the gripping intensity that you must have in a good action sequence.

Action Sequence Example:

Here’s an example of an excellent action sequence; it’s lean, clean, and tight, totally effective,

extremely visual, and not bogged down with details. This is a little piece out of Jurassic Park.

• The scene takes place on the island off Costa Rica just as it has been hit by a violent tropical

storm, and an employee trying to smuggle out dinosaur embryos has shut down the security

systems. The two remote-controlled electric cars, one carrying two children and the attorney

Gennaro, the other the Sam Neill and Jeff Goldblum characters, are stalled next to the massive

electric fence that keeps the dinosaurs enclosed in their restricted area.

• The power is out all over the island, and the kids are scared. They wait nervously. Tim pulls off

the goggles and looks at two clear plastic cups of water that sit in recessed holes on the

dashboard. As he watches, the water in the glasses vibrates, making concentric circles— then

it stops — and then it vibrates again. Rhythmically. Like from footsteps. BOOM. BOOM. BOOM.

• Gennaro’s eyes snap open as he feels it too. He looks up at the rearview mirror. There is a

security pass hanging from it that is bouncing slightly, swaying from side to side. As Gennaro

watches, his image bounces too, vibrating in the rearview mirror. BOOM. BOOM. BOOM.

GENNARO (not entirely convinced) M- Maybe it’s the power trying to come back on. Tim

jumps into the backseat and puts the night goggles on again. He turns and looks out the side

window.

• He can see the area where the goat is tethered. Or was tethered. The chain is still there, but

the goat is gone. BANG! They all jump, and Lex SCREAMS as something hits the Plexiglas

sunroof of the Explorer, hard. They look up. It’s a disembodied goat leg. GENNARO: Oh, Jesus.

Jesus. When Tim whips around to look out the side window again his mouth opens wide but

no sound comes out.

• Through the goggles he sees an animal claw, a huge one, gripping the cables of the “electrified”

fence. He whips off his goggles and pressesforward, against the window. He looks up, up, then

cranes his head back farther, to look out the sunroof. Past the goat’s leg, he can see—

Tyrannosaurus Rex.

• It stands maybe twenty-five feet high, forty feet long from nose to tail, with an enormous,

boxlike head that must be five feet long by itself. The remains of the goat are hanging out of

the Rex’s mouth. It tilts its head back and swallows the animal in one big gulp.

Generally, a good action sequence builds slowly, image by image, word by word, setting things up, drawing us into the excitement as the action gets faster and faster. Good pacing allows the tension to build upon itself.

Action and character, joined together, sharpens the focus of your screenplay and makes

it both a better reading and a better viewing experience. The sequence is a major building block in laying out the story. The next step is building your screenplay.

Chapter 12: Building the storyline

How do we build our story line?

Up until now we’ve discussed the four basic elements that are needed to write a screenplay—ending, beginning, Plot Point I, and Plot Point II. Before you can write the words Fade In, before you can put one word of screenplay down on paper, you need to know those four things.

Each act is a unit, or block, of dramatic action, held together with the dramatic context: Set-Up, Confrontation, Resolution.

Act 1

• Act I is a unit of dramatic (or comédie) action that goes from the beginning of the screenplay

to the Plot Point at the end of Act I. There is a beginning and an end point. Therefore, it is a

whole, complete unto itself, even though Act I is a part of the whole (the screenplay).

• As a complete unit of action, there is a beginning of the beginning, a middle of the beginning,

and an end of the beginning. It is a self-contained unit, approximately twenty to twenty-five

pages long, depending on the screenplay.

• The end is Plot Point I: the incident, episode, or event that hooks into the action and spins it

around in another direction, in this case, Act II. The dramatic context, which holds the content

in place, is the Set-Up. In this unit of dramatic action you set up your story—introduce the

main character, establish the dramatic premise (what the story is about), and sketch in the

dramatic situation, either visually or dramatically.

Act 2

• Act II is also a whole, a complete, self-contained unit of dramatic (or comédie) action; it is the

middle of your screenplay and contains the bulk of the action. It begins at the end of Plot Point

I and continues through to the Plot Point at the end of Act II.

• So we have a beginning of the middle, a middle of the middle, and an end of the middle. It is

approximately sixty pages long, and the Plot Point at the end of Act II occurs approximately

between pages 80 and 90 and spins the action around into Act III.

• The dramatic context is Confrontation, and in this unit of dramatic action your character

encounters obstacle after obstacle that keeps him/her from achieving his/her dramatic need.

Act 3

• Like Acts I and II, Act III is a whole, a self-contained unit of dramatic (or comédie) action. As

such, there is a beginning of the end, a middle of the end, and an end of the end. It is

approximately twenty to thirty pages long, and the dramatic context is Resolution. Resolution,

remember, means “solution,” and refers not to the specific scenes or shots that end your

screenplay, but to what resolves the story line.

In each act, you start from the beginning of the act and move toward the Plot Point at the end

of the act. That means each act has a direction, a line of development that begins at the beginning and ends at the Plot Point. The Plot Points at the end of Acts I and II are your destination points; that’s where you’re going as you’re building or constructing your screenplay.

Chapter 13: The cards

How do you build your storyline? By using 3 X 5 cards.

• Take a pack of 3 X 5 cards.

• Write the idea of each scene or sequence on a single card, and a few brief words of description

(no more than five or six) to aid you while you’re writing.

• You need fourteen cards per thirty pages of screenplay. More than fourteen means you

probably have too much material for Act I; less than fourteen means you may be too thin and

need to add a few more scenes to fill out the Set-Up.

Building the screenplay is different from writing the screenplay. They are two different

processes.

Apples and oranges: It’s very important to remember that when you’re doing the cards,

you’re doing the cards. When you’re writing the screenplay, you’re writing the screenplay. One’s an apple, the other’s an orange.

14 cards: I suggest using fourteen cards per approximately thirty pages of screenplay. That means fourteen cards for Act I, fourteen cards for the First Half of Act II, fourteen cards for the Second Half of Act II, and fourteen cards for Act III. Why fourteen? Because it works.

You have absolute freedom to change, add, or delete. You can arrange or rearrange them, any way you want, adding some, omitting others.

When you first lay down your story line, I suggest you simply write down all those scenes you know you want included in the script. Just scribble a few words that will identify the scene and throw them down in no real order, free-association style.

You already know your beginning and Plot Point I: Cards 1 and 14. That means you already have two cards, the beginning point and the end point. All you need are twelve more to lay out the action line of Act I.

Newton’s Third Law of Motion: “For every action there is an equal and opposite

reaction”.

How to use the cards

• Dramatic need: First, you must know the dramatic need of your main character. What does

your main character want to win, gain, get, or achieve during the course of your screenplay?

This can apply to each scene as well. Once you establish your character’s dramatic need, then

you can create obstacles to that need.

• Action-reaction—it’s a law of the universe. If your character acts in your screenplay,

somebody, or something, is going to react in such a way that your character then reacts—thus

creating a new action that will create another reaction.

• The essence of character is action; your character must act, not merely react.

• If you take great screenplays like The Shawshank Redemption, Lord of the Rings, Seabiscuit,

American Beauty, Y Tu Mamâ También, Thelma & Louise, and The Silence of the Lambs, all the

major ingredients of the story line are set up and either in place or referred to within the first

ten-page unit of dramatic action. The dramatic elements are simple and direct.

• Step by step, scene by scene, build your story from the beginning to the Plot Point at the end

of the act.

• In the fourteen cards you’ve indicated the flow of dramatic action in Act I through the end of

Plot Point I. When you’ve completed the cards for Act I, take a look at what you’ve got. Go over

the cards, scene by scene, like flash cards. Do it several times. Soon you’ll pick up a definite

flow of action; you’ll change a few words here and a few words there to make it read easier.

Get used to the story line. Tell yourself the story of the first act, the Set- Up.

• When you’ve completed the cards for Act I, put them on a bulletin board, on the wall, or on

the floor, in sequential order. Tell yourself the story from the beginning to the Plot Point at the

end of Act I. Do it over and over again, and pretty soon you’ll begin to weave the story into the

fabric of the creative process. Do the same with Act II.

• Use fourteen cards to get from the beginning of Act II to a possible Mid-Point of the story. The

Mid-Point is a story progression point, an incident, episode, or event that occurs around page

60. It could be a scene or sequence, a major event, or an understanding or line of dialogue. Its

function is to move the story forward

• “The things you try that don’t work will always tell you what does work.” It’s a classic rule in

film.

• You know your story from start to finish. It should move smoothly from beginning to end, with

story progressions clearly in mind so all you have to do is look at the cards, close your eyes,

and see the story unfolding.

Chapter 14: Screenplay form

• The writer’s job is to write the screenplay and keep the reader turning pages, not to determine

how a scene or sequence should be filmed. You don’t have to tell the director and cinematographer and film editor how to do their jobs. Your job is to write the screenplay, to

give them enough visual information so they can bring those words on the page into life, in full

“sound and fury,” revealing strong visual and dramatic action, with clarity, insight, and

emotion.

• That’s what the screenplay form is all about—what is a professional screenplay, and what isn’t.

As a reader, I’m always looking for an excuse not to read a script.

• The screenwriter is not responsible for writing in the camera angles and detailed shot

terminology. It’s not the writer’s job. The writer’s job is to tell the director what to shoot, not

how to shoot it. If you specify how each scene should be shot, the director will probably throw

it away.

• The description paragraph should deal only with what we see. If we can’t see it through hand

or facial gestures, or hear it through the dialogue, don’t write it.

• The subtext of the scene, what is not said, can sometimes be more important than what is

said. Again, dialogue serves two basic functions in the scene: Either it moves the story forward

or it reveals information about the character.

• Descriptions of characters or places should not be longer than a few lines. And descriptive

paragraphs, describing the action, should be no longer than four sentences. That’s not a hardand-fast rule, it’s only a suggestion. The more “white space” you can have on the page, the

better it looks.

• New characters introduced are always capitalized.

• The character speaking is always capitalized and placed in the center of the page.

Chapter 15: Writing the screenplay

Recap

• In the beginning, we talked about creating a subject, like three guys stealing moon rocks from

Houston’s NASA facility.

• We broke it down into an action and character.

• We talked about choosing a main character and one or two major characters, and channeling

their action into stealing the moon rocks.

• We talked about determining our ending, our beginning, the Plot Points at the end of Acts I

and II. Then we discussed building the story line with 3 X 5 cards, focusing on the direction,

the line of development, we wish to follow.

Look at the paradigm: WE KNOW WHAT TO WRITE! We’ve completed a form of preparation applicable to all writing in general, and the screenplay in particular; it is form, structure, and character. You are now able to select the elements of your story that fall inside the paradigm of screenplay form and begin the journey of writing it from beginning to end. In other words, you know what to write; now all you’ve got to do is write it.

Carry the cards with you, so you can go over the material when you’re standing in line

or riding on the subway, bus, or train.

Set goals: Writing is a day-by-day job—shot by shot, scene by scene, page by page, day by day.

Set goals for yourself. Three pages a day is reasonable and realistic.

Establish a writing schedule: 10:30 to noon; or 8 to 10 P.M.

Resistance: One of my favorite forms of resistance is sitting down to write and suddenly getting an idea for another screenplay—a much better idea, an idea so unique, so original, so exciting, you wonder what you’re doing writing this screenplay. You really think about it. You may even get two or three “better” ideas. It happens quite often; it may be a great idea, but it’s still a form of resistance! If it’s really a good idea, it will keep. Simply write it up in a page or two, put it in a file marked “New Projects,” and file it away.

Fighting the resistance: We’re masters at creating reasons and excuses not to write; it’s

simply a barrier to the creative process. So, how do you deal with it? Simple. If you know it’s going to happen, simply acknowledge it when it does. Don’t put yourself down, feel guilty, feel worthless, or punish yourself in any way. Just acknowledge the resistance—then move right through to the other side. The first ten pages are the most difficult. Your writing is going to be awkward, stilted, and probably not very good. It’s okay.

Dialogue

Dialogue is a function of character: Remember that dialogue is a function of

character. Let’s review the purpose of dialogue:

• Moves the story forward

• Reveals information about the characters—after all, they do have a history

• Communicates necessary facts and information to the reader

• Establishes character relationships, making them real, natural, and spontaneous

• Gives your characters depth, insight, and purpose

• Reveals the conflicts of the story and characters

• Reveals the emotional states of your characters

• Comments on the action

Characters start talking to you: It takes anywhere from forty to fifty pages before

your characters start talking to you. And they do start talking to you. Let yourself write shitty pages, with stilted, direct, dumb, and obvious dialogue. Don’t worry about it. Just keep writing. Dialogue can always be cleaned up during the rewrite. “Writing is rewriting” is the ancient adage.

New scenes: I said in Chapter 12 that one card equals one scene, but when you’re writing the

screenplay, that will be contradictory. You’ll suddenly “discover” a new scene that works better or that you hadn’t thought of. Use it. It will lead you to veer off the path of the cards into a few new scenes or sequences that you hadn’t even considered.

It doesn’t matter if you want to drop scenes or add new ones; just do it. Your creative mind has

assimilated the cards so you can throw out a few scenes and still be following the direction of your story. When you’re doing the cards, you’re doing the cards. When you’re writing the screenplay, you’re writing the screenplay.

All drama is conflict: without conflict, you have no action; without action you have no

character; without character, you have no story. And without story, you have no screenplay. Dramatic conflict can be either internal or external:

External conflict is where the conflict is outside the characters and they face physical (and of course, emotional) obstacles.

Creating conflict within the story, through the characters and events, is one of those simple, basic “truths” of all writing, whether it be novel, play, or screenplay.

Conflict can be anything: a struggle, a quarrel, a battle, or a chase scene; fear of life, or fear of failure or success; internal or external— any kind of confrontation or obstacle, and it really doesn’t matter whether it’s emotional, physical, or mental. Conflict must be at the very hub of your story, because it is the core of strong action and strong character.

3 stages

You’re going to move through three stages of your first-draft screenplay.

“Words on paper” – stage

• The first stage is the “words on paper” stage. That’s when you put it all down—everything.

During this stage, if you’re in doubt about writing a scene or not writing it, write it. If in doubt,

write.

• Keep moving forward in your story. If you write a scene and go back to clean it up, polish it,

and “make it right,” you’ll find you’ve dried up at about page 60, lost all your creative spark.

Any major changes you need to make, do in the second draft.

• There will be moments when you don’t know how to begin a scene, or what to do next. If this

happens, break down the action of your scene into a beginning, middle, and end. What’s the

purpose of the scene? Where does your character come from? What is his/her purpose in the

scene? Ask yourself “What happens next?” and you’ll get an answer.

• There’s only one rule that governs your writing—not whether it’s “good” or “bad,” but does it

work? Does your scene or sequence work? If it does, keep it in.

• If you get stuck, go back to your characters; go into your character biography and ask him/her

what he or she would do in that situation. You’ll get an answer.

• Sometimes you’ll get into a scene and not know where you’re going, or what you’re looking

for to make it work. You know the context, not the content. So you’ll write the same scene five

different times, from five different points of view, and out of all these attempts you may find

one line that gives you the key to what you’re looking for.

• Around page 80 or 90, the resolution is forming and you’ll discover the screenplay is literally

writing itself. You’re just the medium, putting in time to finish the script. You don’t have to do

anything; if you let it come through you, it writes itself.

Taking a cold, hard, objective look at what you’ve written.

• The second stage of your first draft is: taking a cold, hard, objective look at what you’ve written.

• Reduce it to 130 or 140 pages. You’ll cut out some scenes, add new ones, rewrite others, and

make any changes you need to, to get it into a workable form.

• It might take you about three weeks to do this. When you’ve finished, you’re ready to approach

the third stage of your first-draft script.

Where the story really gets written

• This is where you see what you’ve got, where the story really gets written. You’ll polish it,

accent it, hone and rewrite it, trim it to length, and make it all come to life.

• In this stage you may rewrite a scene as many as ten times before you get it right. There will

always be one or two scenes that don’t work the way you want them to, no matter how many

times you rewrite them.

• You know these scenes don’t work, but the reader will never know. He/she reads for story

and execution, not content.

“Best scene” file: Create a “best scene” file where I put the “best” things I’ve ever written,

things I had to cut out to tighten the script. You have to be ruthless in writing a screenplay. If it doesn’t work, it doesn’t work. If your scenes stand out and draw attention to themselves, they might impede the flow of action. Scenes that stand out and work are the scenes that will be remembered. Every good film has one or possibly two scenes that people always remember.

Writers block

• The first thing to do is to admit you have a problem and that it’s not going to go away until you

deal with it, confront it head-on. That’s just one of the truths of life.

• When you reach this kind of crisis point, you’re so overwhelmed and frustrated that you have

to regroup. Just stop writing. Put down your pen and paper, shut off your computer or tape

recorder, however you’re working, and spend some time contemplating your story: What is

the story about? What is the dramatic need of your main character? How are you going to

resolve the story line? The answers to these questions are the key to getting back on track.

• Take out a separate piece of paper and label it The Critic’s Page. As you start writing the script,

every time you become aware of a negative comment, thought, or judgment, just write it down

on The Critic’s Page. Number the comments, label them, just as if you were keeping a journal

or making a shopping list. You might become aware of such comments as “These pages are

terrible,” or “I don’t really know what I’m doing,

• The first day you’re doing The Critic’s Page, you may write two pages of screenplay and four

pages of critical comments. On the second day maybe you’ll write three pages of screenplay

and two or more pages on The Critic’s Page. The third day maybe you’ll do four or five pages

of screenplay and a couple of pages of the critic.

• At this point, stop writing. The next day, take the critic’s pages, put them in order, and read

them: all your negative comments for day one, day two, day three. As you think about these

comments, mull them over in your mind. As you look these pages over, you’ll discover

something very interesting: The critic always says the same thing.

• What you try that doesn’t work will always show you what does work. As you struggle through

your problem area, just get something down on paper; just write lousy pages. You’ll always be

able to go back and make them better.

• Until you become aware of the critic’s voice running around in the back of your mind, you’re

going to become a victim of that voice.

• See the ordeal as part of the writer’s experience. After all, it’s universal, everybody goes

through it; it’s nothing new or unusual. If you recognize and acknowledge that, you’ve reached

a creative crossroads. The realization becomes a creative guide to another level of your

screenwriting craft.

• You’re going to have to stop writing, go back into your character’s life and action, and define

and clarify different elements of your character’s life. You’re going to have to go back and do

new character biographies; to define or redefine the characters and their relationships to each

other, which are, after all, the hub of your story line.

Silence: The art of screenwriting is finding places where silence works better than words.

Just a few lines: You don’t need pages and pages of dialogue to set up, explain, or move your

story forward; just a few lines will do, if you enter the scene at the right point.

Chapter 16: After it´s written

After first draft: After you complete the first “words on paper” draft, put it aside for a week.

Then go back and reread the material from beginning to end in one sitting. You don’t want to take any notes as you read. You just want to read.

The three essays

1. After you’ve finished reading the script, put it away again. Now write three essays. The first

essay, in free association, is to write what first attracted you to the material. Do this in two or

three pages, more if you choose. Was it the character, the situation, the idea, or the action line that originally attracted you to the material? Just answer this question: What really attracted you to the material? Throw down your thoughts, words, and ideas.

2. The second essay, also in free association, answers this question: What kind of a screenplay

did you actually end up writing? You may have started to write a mystery-thriller with a strong

love interest and ended up writing a love story with a strong mystery-thriller aspect.

We want a clean, coherent narrative through line in the screenplay. Write this second essay in

two or three pages.

3. In this third essay, you want to answer this question: What do you have to do to change what

you did write into what you wanted to write? In other words, intention must equal result.

After the essays

When you’ve finished these three essays, think about what you have to do to strengthen and solidify your story line so your intention equals your result. Now read the first “words on paper” draft in units of dramatic action.

Read Act I and make notes in the margins. Out of twenty or so scenes, you’ll find you can keep ten of them intact. Of the remaining ten, you may have to change the focus in five or six of them by rewriting dialogue and possibly adding some action, and you may see that the remaining five scenes don’t work at all.

So, you’ll have to write five new scenes. All in all, you may have to change anywhere from 65 to 80 percent of Act I. Just do it. You’ve spent several months working on this script, so you want to do it right.

Clean script: Your script must be clean, neat, and professional-looking, meaning it’s got to be

in correct industry format, with Courier 10 or 12 font. The form of your screenplay must be correct.

The title page: The title page is the title page. It should be simple and direct: “The Title” should be in the middle of the page, “A Screenplay by John Doe” directly under it, and your address or phone number in the lower-right-hand corner.

No synopsis: Do not send a synopsis of your script along with your material; it will not be read.

The reader: Usually, a screenplay has to pass the gauntlet of”The Reader.” Decisions about

whether or not to seriously consider a particular screenplay are usually based on this reader’s

comments.