What is the summary of Quiet?

The book summary of Quiet by Susan Cain contains my own personal notes from the book. I think that both introverts and extroverts can learn a lot from it. Because it´s when both mindsets understand and accept each other that magic happen.

In the summary of Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking, Susan Cain writes about the ideal of the extrovert and how it often is considered to be synonymous with good leadership. Another question that you´ll read about in the summary of Quiet is whether introverts have inherited their temperament or if cultural factors are more important.

I´m not going to give anything away – you´ll have to read Susan Cains book – but I hope that you will have use for this summary both as a practical tool and as a source of inspiration.

Facts about the summary of Quiet

Book title: Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking

Book Author: Susan Cain

Summary pages: 21

Year: 2013

Genre: Psychology

Download summary of Quiet by Susan Cain

More about the summary of Quiet

Take the Quiz and see if you are an introvert at the website for Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking. Below you can watch Susan Cains TED Talk about introverts:

[ted id=1377]

Read the summary of Quiet

This is the summary of Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking by Susan Cain. See further up on the page if you want to download the summary of Quiet as a pdf instead of reading it directly on the website.

Introduction – The North and South of Temperament

The Extrovert Ideal: the Extrovert Ideal—the omnipresent belief that the ideal self is

gregarious, alpha, and comfortable in the spotlight. The archetypal extrovert prefers action to

contemplation, risk-taking to heed-taking, certainty to doubt. He favors quick decisions, even at the risk of being wrong. She works well in teams and socializes in groups. We like to think that we value individuality, but all too often we admire one type of individual—the kind who’s comfortable “putting himself out there.

Introverts vs. extroverts: Introverts are drawn to the inner world of thought and feeling,

said Jung, extroverts to the external life of people and activities. Introverts focus on the meaning

they make of the events swirling around them; extroverts plunge into the events themselves.

Introverts recharge their batteries by being alone; extroverts need to recharge when they don’t

socialize enough.

Chapter 1: The rise of the “mighty likeable fellow” – How Extroversion Became the Cultural Ideal

The Culture of Character: In the Culture of Character, the ideal self was serious, disciplined, and honorable. What counted was not so much the impression one made in public as

how one behaved in private.

Chapter 2: The myth of charismatic leadership – The Culture of Personality, a Hundred Years Later

Successful synergy: Successful synergy means a higher ranking for the team than for its

individual members.

How good ideas drown: If we assume that quiet and loud people have roughly the same

number of good (and bad) ideas, then we should worry if the louder and more forceful people always carry the day. This would mean that an awful lot of bad ideas prevail while good ones get squashed. Yet studies in group dynamics suggest that this is exactly what happens.

We perceive talkers as smarter than quiet types: Even though grade-point averages and SAT and intelligence test scores reveal this perception to be inaccurate. In one experiment in which two strangers met over the phone, those who spoke more were considered more intelligent, better looking, and more likable.

We also see talkers as leaders: The more a person talks, the more other group

members direct their attention to him, which means that he becomes increasingly powerful as a

meeting goes on. It also helps to speak fast; we rate quick talkers as more capable and appealing

than slow talkers. We don’t need giant personalities to transform companies. We need leaders who build not their own egos but the institutions they run.

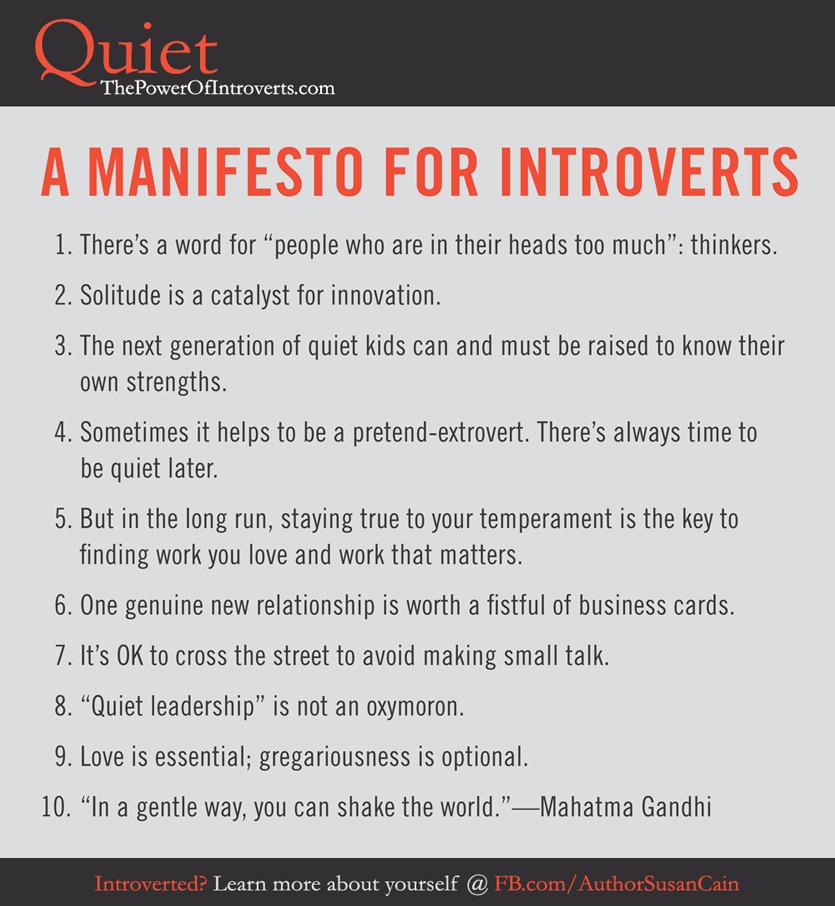

Introverts are good leaders: Introverts are uniquely good at leading initiative-takers.

Because of their inclination to listen to others and lack of interest in dominating social situations, introverts are more likely to hear and implement suggestions.

Having benefited from the talents of their followers, they are then likely to motivate them to be even more proactive. Extroverts, on the other hand, can be so intent on putting their own stamp on events that they risk losing others’ good ideas along the way and allowing workers to lapse into passivity.

Chapter 3: When collaboration kills creativity – The Rise of the New Groupthink and the Power of Working Alone

Creative people as introverts: Creative people tend to be socially poised introverts.

They are interpersonally skilled but “not of an especially sociable or participative temperament.”

They often describe themselves as independent and individualistic. As teens, many had been shy and solitary.

Introverts are independent: Introverts prefer to work independently, and solitude can

be a catalyst to innovation. As the influential psychologist Hans Eysenck once observed, introversion “concentrates the mind on the tasks in hand, and prevents the dissipation of energy on social and sexual matters unrelated to work.”

The New Groupthink: The New Groupthink elevates teamwork above all else. It insists that

creativity and intellectual achievement come from a gregarious place.

The key to exceptional achievement – Deliberate Practice: What’s so magical about solitude? In many fields, Ericsson told me, it’s only when you’re alone that you can engage in Deliberate Practice, which he has identified as the key to exceptional achievement.

When you practice deliberately, you identify the tasks or knowledge that are just out of your reach, strive to upgrade your performance, monitor your progress, and revise accordingly. Practice sessions that fall short of this standard are not only less useful—they’re counterproductive.

They reinforce existing cognitive mechanisms instead of improving them. Deliberate Practice is best conducted alone for several reasons. It takes intense concentration, and other people can be

distracting. It requires deep motivation, often self-generated. But most important, it involves

working on the task that’s most challenging to you personally.

Only when you’re alone, Ericsson told me, can you “go directly to the part that’s challenging to you. If you want to improve what you’re doing, you have to be the one who generates the move.

Multitasking: Scientists now know that the brain is incapable of paying attention to two things

at the same time. What looks like multitasking is really switching back and forth between multiple tasks, which reduces productivity and increases mistakes by up to 50 percent.

Peer pressure: If personal space is vital to creativity, so is freedom from “peer pressure.”

Group size: Studies have shown that performance gets worse as group size increases: groups of

nine generate fewer and poorer ideas compared to groups of six, which do worse than groups of

four.

Online collaboration: we’re so impressed by the power of online collaboration that we’ve

come to overvalue all group work at the expense of solo thought. We fail to realize that participating in an online working group is a form of solitude all its own. Instead we assume that the success of online collaborations will be replicated in the face-to-face world.

The failure of brainstorming: Psychologists usually offer three explanations for the failure of group brainstorming.

– The first is social loafing: in a group, some individuals tend to sit back and let others do the

work.

– The second is production blocking: only one person can talk or produce an idea at once,

while the other group members are forced to sit passively.

– And the third is evaluation apprehension, meaning the fear of looking stupid in front of

one’s peers.

Introvert-extrovert relationships: we should actively seek out symbiotic introvert-extrovert relationships, in which leadership and other tasks are divided according to people’s natural strengths and temperaments. The most effective teams are composed of a healthy mix of introverts and extroverts.

Chapter 4: Is temperament destiny? Nature, Nurture, and the Orchid Hypothesis

Temperament” and personality: Psychologists often discuss the difference between

“temperament” and “personality.” Temperament refers to inborn, biologically based behavioral and emotional patterns that are observable in infancy and early childhood; personality is the complex brew that emerges after cultural influence and personal experience are thrown into the mix. Some say that temperament is the foundation, and personality is the building.

The amygdala: serves as the brain’s emotional switchboard, receiving information from the

senses and then signaling the rest of the brain and nervous system how to respond.

The more reactive a child’s amygdala, the higher his heart rate is likely to be, the more widely dilated his eyes, the tighter his vocal cords, the more cortisol (a stress hormone) in his saliva—the more jangled he’s likely to feel when he confronts something new and stimulating.

Inherited introversion: introversion and extroversion, like other major personality traits

such as agreeableness and conscientiousness, are about 40 to 50 percent heritable. We are born with prepackaged temperaments that powerfully shape our adult personalities.

Internalizing parents’ standards of conduct: Many psychologists believe that children develop a conscience when they do something inappropriate and are rebuked by their caregivers. Disapproval makes them feel anxious, and since anxiety is unpleasant, they learn to steer clear of antisocial behavior. This is known as internalizing their parents’ standards of conduct, and its core is anxiety.

The orchid hypothesis by David Dobbs: This theory holds that many children are

like dandelions, able to thrive in just about any environment. But others, including the high-reactive types that Kagan studied, are more like orchids: they wilt easily, but under the right conditions can grow strong and magnificent.

The reactivity of these kids’ nervous systems makes them quickly overwhelmed by childhood

adversity, but also able to benefit from a nurturing environment more than other children do. In

other words, orchid children are more strongly affected by all experience, both positive and negative.

High-reactive: High-reactive kids who enjoy good parenting, child care, and a stable home

environment tend to have fewer emotional problems and more social skills than their lower-reactive peers, studies show. Often they’re exceedingly empathic, caring, and cooperative. They work well with others. They are kind, conscientious, and easily disturbed by cruelty, injustice, and irresponsibility. They’re successful at the things that matter to them. They don’t necessarily turn into class presidents or stars of the school play.

A high-reactive child’s ideal parent: someone who “can read your cues and respect

your individuality; is warm and firm in placing demands on you without being harsh or hostile;

promotes curiosity, academic achievement, delayed gratification, and self-control; and is not harsh, neglectful, or inconsistent.”

Chapter 5: Beyond temperament The Role of Free Will – And the Secret of Public Speaking for Introverts

An fMRI machine: can measure which parts of the brain are active when you’re thinking a

particular thought or performing a specific task.

Temperament: the footprint of a high- or low-reactive temperament never disappeared in

adulthood.

Personalities: we can stretch our personalities, but only up to a point. Our inborn temperaments influence us, regardless of the lives we lead.

The rubber band theory of personality: We are like rubber bands at rest. We are elastic and can stretch ourselves, but only so much.

Introverts are more sensitive: there’s a host of evidence that introverts are more

sensitive than extroverts to various kinds of stimulation, from coffee to a loud bang to the dull roar of a networking event—and that introverts and extroverts often need very different levels of

stimulation to function at their best.

Sweet spots: You can organize your life in terms of what personality psychologists call “optimal levels of arousal” and what I call “sweet spots,” and by doing so feel more energetic and alive than before. Your sweet spot is the place where you’re optimally stimulated. People who are aware of their sweet spots have the power to leave jobs that exhaust them and start new and satisfying businesses.

Sleep deprivation: introverts function better than extroverts when sleep deprived.

Chapter 6: Franklin was a politician, but Eleanor spoke out of conscience – Why Cool Is Overrated

The highly sensitive: tend to be philosophical or spiritual in their orientation, rather than

materialistic or hedonistic. They dislike small talk. They often describe themselves as creative or

intuitive (just as Aron’s husband had described her). They dream vividly, and can often recall their dreams the next day. They love music, nature, art, physical beauty.

They feel exceptionally strong emotions—sometimes acute bouts of joy, but also sorrow,

melancholy, and fear. Highly sensitive people also process information about their environments — both physical and emotional — unusually deeply. They tend to notice subtleties that others miss — another person’s shift in mood, say, or a light bulb burning a touch too brightly.

Sensitive people: is sometimes highly empathic. It’s as if they have thinner boundaries

separating them from other people’s emotions and from the tragedies and cruelties of the world.

They tend to have unusually strong consciences. They avoid violent movies and TV shows; they’re acutely aware of the consequences of a lapse in their own behavior. In social settings they often focus on subjects like personal problems, which others consider “too heavy.”

Guilt: the ones who are likely to be introverts who feel the guiltiest. “Functional, moderate guilt,” writes Kochanska, “may promote future altruism, personal responsibility, adaptive behavior in school, and harmonious, competent, and prosocial relationships with parents, teachers, and friends.”

High-reactive introverts: Among the tools tests researchers use to measure personality

traits are skin conductance tests, which record how much people sweat in response to noises, strong emotions, and other stimuli. High-reactive introverts sweat more; low-reactive extroverts sweat less. Their skin is literally “thicker,” more impervious to stimuli, cooler to the touch.

Acts of devotion: Keltner has tracked the roots of human embarrassment and found that

after many primates fight, they try to make up. They do this partly by making gestures of

embarrassment of the kind we see in humans—looking away, which acknowledges wrongdoing and the intention to stop; lowering the head, which shrinks one’s size; and pressing the lips together, a sign of inhibition. These gestures in humans have been called “acts of devotion,

Embarrassment: “Embarrassment reveals how much the individual cares about the rules that

bind us to one another.”

Slow-starters: approximately 20 percent of the members of many species are “slow to warm

up,” while the other 80 percent are “fast” types who venture forth boldly without noticing much of what’s going on around them.

Slow animals are best described as shy, sensitive types. They don’t assert themselves, but they are observant and notice things that are invisible to the bullies. They are the writers and artists at the party who have interesting conversations out of earshot of the bullies. They are the inventors who figure out new ways to behave, while the bullies steal their patents by copying their behavior.

Extroverts vs. Introverts: consider this trade-off: human extroverts have more sex partners than introverts do—a boon to any species wanting to reproduce itself—but they commit more adultery and divorce more frequently, which is not a good thing for the children of all those

couplings. Extroverts exercise more, but introverts suffer fewer accidents and traumatic injuries.

Extroverts enjoy wider networks of social support, but commit more crimes.

Sensitive people: tend to speak softly because that’s how they prefer others to communicate

with them.

Small talk: In most settings, people use small talk as a way of relaxing into a new relationship,

and only once they’re comfortable do they connect more seriously. Sensitive people seem to do the reverse. They “enjoy small talk only after they’ve gone deep,” says Strickland.

Chapter 7: Why did Wall Street crash and warren Buffett prosper? – How Introverts and Extroverts Think (and Process Dopamine) Differently

Reward sensitivity: A reward-sensitive person is highly motivated to seek rewards—from a

promotion to a lottery jackpot to an enjoyable evening out with friends. Reward sensitivity motivates us to pursue goals like sex and money, social status and influence. It prompts us to climb ladders and reach for faraway branches in order to gather life’s choicest fruits.

But sometimes we’re too sensitive to rewards. Reward sensitivity on overdrive gets people into all kinds of trouble. We can get so excited by the prospect of juicy prizes, like winning big in the stock market, that we take outsized risks and ignore obvious warning signals.

Extroverted clients are more likely to be highly reward-sensitive, while the introverts are more likely to pay attention to warning signals. They’re more successful at regulating their feelings of desire or excitement. They protect themselves better from the downside.

Discipline: The introverts are much better at making a plan, staying with a plan, being very

disciplined.

Extroverts seek rewards: Extroverts, in other words, are characterized by their tendency

to seek rewards, from top dog status to sexual highs to cold cash. They’ve been found to have

greater economic, political, and hedonistic ambitions than introverts; even their sociability is a

function of reward-sensitivity, according to this view—extroverts socialize because human

connection is inherently gratifying.

Extroverts seek a rush: Extroverts, in other words, often find themselves in an emotional

state we might call “buzz”—a rush of energized, enthusiastic feelings. This is a sensation we all know and like, but not necessarily to the same degree or with the same frequency: extroverts seem to get an extra buzz from the pursuit and attainment of their goals.

Dopamine: is the “reward chemical” released in response to anticipated pleasures. Extroverts’

dopamine pathways appear to be more active than those of introverts.

Delaying gratification: Introverts also seem to be better than extroverts at delaying

gratification, a crucial life skill associated with everything from higher SAT scores and income to

lower body mass index.

Introverts are “geared to inspect” and extroverts “geared to respond.”

Extroverts and goals: If you focus on achieving your goals, as reward-sensitive extroverts

do, you don’t want anything to get in your way—neither naysayers nor the number nine. You speed up in an attempt to knock these roadblocks down. Yet this is a crucially important misstep, because the longer you pause to process surprising or negative feedback, the more likely you are to learn from it.

Introverts and goals: Introverts, in contrast, are constitutionally programmed to downplay

reward—to kill their buzz, you might say—and scan for problems. “As soon they get excited,” says Newman, “they’ll put the brakes on and think about peripheral issues that may be more important.

Introverts seem to be specifically wired or trained so when they catch themselves getting excited and focused on a goal, their vigilance increases.” Introverts also tend to compare new information with their expectations, he says. They ask themselves, “Is this what I thought would happen? Is it how it should be?”

Where extroverts do better: on many kinds of tasks, particularly those performed

under time or social pressure or involving multitasking, extroverts do better. Extroverts are better than introverts at handling information overload. Introverts’ reflectiveness uses up a lot of cognitive capacity, according to Joseph Newman.

Cognitive capacity: Extroverts appear to allocate most of their cognitive capacity to the goal

at hand, while introverts use up capacity by monitoring how the task is going. But introverts seem to think more carefully than extroverts, as the psychologist Gerald Matthews describes in his work.

Problem-solving: Extroverts are more likely to take a quick-and-dirty approach to problem solving, trading accuracy for speed, making increasing numbers of mistakes as they go, and abandoning ship altogether when the problem seems too difficult or frustrating. Introverts think before they act, digest information thoroughly, stay on task longer, give up less easily, and work more accurately.

Attention: Introverts and extroverts also direct their attention differently: if you leave them to

their own devices, the introverts tend to sit around wondering about things, imagining things,

recalling events from their past, and making plans for the future. The extroverts are more likely to focus on what’s happening around them. It’s as if extroverts are seeing “what is” while their

introverted peers are asking “what if.”

Einstein: “It’s not that I’m so smart,” said Einstein, who was a consummate introvert. “It’s that I stay with problems longer.”

Flow: The key to flow is to pursue an activity for its own sake, not for the rewards it brings.

Although flow does not depend on being an introvert or an extrovert, many of the flow experiences that Csikszentmihalyi writes about are solitary pursuits that have nothing to do with reward-seeking: reading, tending an orchard, solo ocean cruising.

Flow often occurs, he writes, in conditions in which people “become independent of the social

environment to the degree that they no longer respond exclusively in terms of its rewards and

punishments. To achieve such autonomy, a person has to learn to provide rewards to herself.”

Introverts and flow: If you’re an introvert, find your flow by using your gifts. You have the

power of persistence, the tenacity to solve complex problems, and the clear-sightedness to avoid

pitfalls that trip others up. You enjoy relative freedom from the temptations of superficial prizes like money and status. Indeed, your biggest challenge may be to fully harness your strengths.

You may be so busy trying to appear like a zestful, reward-sensitive extrovert that you undervalue your own talents, or feel underestimated by those around you. But when you’re focused on a project that you care about, you probably find that your energy is boundless.

Chapter 8: Soft power Asian-Americans and the Extrovert Ideal

Quiet persistence: requires sustained attention—in effect restraining one’s reactions to

external stimuli. Excellent students seem not only to possess the cognitive ability to solve math and science problems, but also to have a useful personality characteristic: quiet persistence.

Chapter 9: When should you act more extroverted than you really are?

The “person-situation” debate: Do fixed personality traits really exist, or do they shift

according to the situation in which people find themselves?

Free Trait Theory: Little believes that fixed traits and free traits coexist. According to Free

Trait Theory, we are born and culturally endowed with certain personality traits—introversion, for example—but we can and do act out of character in the service of “core personal projects.” In other words, introverts are capable of acting like extroverts for the sake of work they consider important, people they love, or anything they value highly.

Core personal projects: According to Little, our lives are dramatically enhanced when

we’re involved in core personal projects that we consider meaningful, manageable, and not unduly stressful, and that are supported by others. When someone asks us “How are things?” we may give a throwaway answer, but our true response is a function of how well our core personal projects are going.

Behavioral leakage: there’s a limit to how much we can control our self-presentation. This is

partly because of a phenomenon called behavioral leakage, in which our true selves seep out via

unconscious body language: a subtle look away at a moment when an extrovert would have made eye contact, or a skillful turn of the conversation by a lecturer that places the burden of talking on the audience when an extroverted speaker would have held the floor a little longer.

Suppressing negative emotions: One noteworthy study suggests that people who suppress negative emotions tend to leak those emotions later in unexpected ways.

“People who tend to [suppress their negative emotions] regularly, might start to see the world in a more negative light.”

Chapter 10: The communication gap – How to Talk to Members of the Opposite Type

The need for intimacy: introverts and extroverts are differently social. What psychologists

call “the need for intimacy” is present in introverts and extroverts alike. In fact, people who value intimacy highly don’t tend to be, as the noted psychologist David Buss puts it, “the loud, outgoing, life-of-the-party extrovert.”

They are more likely to be someone with a select group of close friends, who prefers “sincere and

meaningful conversations over wild parties.” They are more likely to be someone like Emily.

Conversely, extroverts do not necessarily seek closeness from their socializing. “Extroverts seem to need people as a forum to fill needs for social impact, just as a general needs soldiers to fill his or her need to lead,”

Introverts vs. extroverts: introverts like people they meet in friendly contexts; extroverts

prefer those they compete with.

Extroverts are sociable because their brains are good at handling competing demands on their

attention—which is just what dinner-party conversation involves. In contrast, introverts often feel repelled by social events that force them to attend to many people at once.

When introverts assume the observer role: as when they write novels, or

contemplate unified field theory—or fall quiet at dinner parties—they’re not demonstrating a failure of will or a lack of energy. They’re simply doing what they’re constitutionally suited for. When introverts are able to experience conversations in their own way, they make deep and enjoyable connections with others.

Chapter 11: On cobblers and generals – How to Cultivate Quiet Kids in a World That Can’t Hear Them

An introverted child’s reaction to novelty: One of the best things you can do for

an introverted child is to work with him on his reaction to novelty. Remember that introverts react not only to new people, but also to new places and events. So don’t mistake your child’s caution in new situations for an inability to relate to others. He’s recoiling from novelty or overstimulation, not from human contact.

Expose gradually: The key is to expose your child gradually to new situations and people—

taking care to respect his limits, even when they seem extreme. This produces more confident kids than either overprotection or pushing too hard. Let him know that his feelings are normal and natural, but also that there’s nothing to be afraid of.

Go at your child’s pace; don’t rush him. If he’s young, make the initial introductions with

the other little boy if you have to. And stick around in the background—or, when he’s really little, with a gentle, supportive hand on his back—for as long as he seems to benefit from your presence.

When he takes social risks, let him know you admire his efforts: “I saw you go up to those new kids yesterday. I know that can be difficult, and I’m proud of you. Slowly your child will see that it’s worth punching through her wall of discomfort to get to the fun on the other side. She’ll learn how to do the punching by herself.

Silent reassuring: “If you’re consistent in helping your young child learn to regulate his or her

emotions and behaviors in soothing and supportive ways, something rather magical will begin to

happen: in time, you might watch your daughter seem to be silently reassuring herself: ‘Those kids are having fun, I can go over there.’ He or she is learning to self-regulate fearfulness and wariness.

Shame and shyness: don’t let her hear you call her “shy”: she’ll believe the label and

experience her nervousness as a fixed trait rather than an emotion she can control. She also knows full well that “shy” is a negative word in our society. Above all, do not shame her for her shyness.

School: many schools are designed for extroverts. Introverts need different kinds of instruction

from extroverts. If your child prefers to work autonomously and socialize one-on-one, there’s

nothing wrong with her; she just happens not to fit the prevailing model. The purpose of school

should be to prepare kids for the rest of their lives, but too often what kids need to be prepared for is surviving the school day itself.

Worst of all, there’s little time to think or create. The structure of the day is almost guaranteed to sap his energy rather than stimulate it.

Stops learning: Kids stop learning when they feel emotionally threatened.

Negative public speaking experiences: Experts believe that negative public speaking experiences in childhood can leave children with a lifelong terror of the podium.

Deep interests: Introverts often have one or two deep interests that are not necessarily

shared by their peers. Sometimes they’re made to feel freaky for the force of these passions, when in fact studies show that this sort of intensity is a prerequisite to talent development.

Collaboration: Some collaborative work is fine for introverts, even beneficial. But it should

take place in small groups—pairs or threesomes—and be carefully structured so that each child

knows her role “Forcing highly apprehensive young people to perform orally is harmful,”

The perfect school for an introverted child: look for a school that:

- Prizes independent interests and emphasizes autonomy conducts group activities in

moderation and in small, carefully managed groups - Values kindness, caring, empathy, good citizenship

- Insists on orderly classrooms and hallways

- Is organized into small, quiet classes

- Chooses teachers who seem to understand the shy/serious/introverted/sensitive

temperament - Focuses its academic/athletic/extracurricular activities on subjects that are particularly

interesting to your child - Strongly enforces an anti-bullying program

- Emphasizes a tolerant, down-to-earth culture

- Attracts like-minded peers, for example intellectual kids, or artistic or athletic ones,

depending on your child’s preference.

Introverts often stick with their enthusiasms: While extroverts are more likely

to skate from one hobby or activity to another, introverts often stick with their enthusiasms. This gives them a major advantage as they grow, because true self-esteem comes from competence, not the other way around. Researchers have found that intense engagement in and commitment to an activity is a proven route to happiness and well-being.