Who is the summary of Contagious for?

Contagious: Why Things Catch On summary is for everyone that are interested in the psychology behind why things go viral.

Facts about the summary of Contagious by Jonah Berger

Book Title: Contagious: Why Things Catch On

Book Author: Jonah Berger

Book Year: 2013

Summary pages: 23

Genre: Marketing, Advertising

More about the summary of Contagious

Check out Jonah Berger´s blog which is quite interesting. He continues on the same topic as in the book, discussing word of mouth, virality and sharing mechanics. Also make sure that you have a look at Jonah´s speech at Google below.

Download the summary of Contagious

Read the summary of Contagious

Introduction: Why things catch on

Social epidemics: Instances where products, ideas, and behaviors diffuse through a

population. They start with a small set of individuals or organizations and spread, often from person to person, almost like a virus.

Why: One reason some products and ideas become popular is that they are just plain better. Another reason products catch on is attractive pricing. Advertising also plays a role.

Social transmission

Social influence and word of mouth: People love to share stories, news,

and information with those around them. We tell our friends about great vacation destinations, chat with our neighbors about good deals, and gossip with coworkers about potential layoffs. We write online reviews about movies, share rumors on Facebook, and tweet about recipes we just tried. Social influence has a huge impact on whether products, ideas, and behaviors catch on.

Word of mouth is more effective than traditional advertising for two key reasons. First, it’s more persuasive. Second, word of mouth is more targeted. Companies try to advertise in ways that allow them to reach the largest number of interested customers.

WOM offline vs online: Research by the Keller Fay Group finds that only 7 percent

of word of mouth happens online. We tend to overestimate online word of mouth because it’s easier to see. Social media sites provide a handy record of all the clips, comments, and other content we share online. So when we look at it, it seems like a lot. But we don’t think as much about all the offline conversations we had over that same time period because we can’t easily see them.

Online conversations could reach a much larger audience, but given that offline conversations may be more in-depth, it’s unclear that social media is the better way to go. So the first issue with all the hype around social media is that people tend to ignore the importance of offline word of mouth, even though offline discussions are more prevalent, and potentially even more impactful, than online ones. The second issue is that Facebook and Twitter are technologies, not strategies. Word-of-mouth marketing is effective only if people actually talk.

Harnessing the power of word of mouth, online or offline, requires understanding why people talk and why some things get talked about and shared more than others. The psychology of sharing. The science of social transmission. In The Tipping Point, for example, Malcolm Gladwell argues that social epidemics are driven “by the efforts of a handful of exceptional people” whom he calls mavens, connectors, and salesmen.

Yes, we all know people who are really persuasive, and yes, some people have more friends than others. But in most cases that doesn’t make them any more influential in spreading information or making things go viral.

Joke analogy: To use an analogy, think about jokes. We all have friends who are better joke tellers than we are. Whenever they tell a joke the room bursts out laughing. But jokes also vary. Some jokes are so funny that it doesn’t matter who tells them. Everyone laughs even if the person sharing the joke isn’t all that funny. Contagious content is like that—so inherently viral that it spreads regardless of who is doing the talking.

Virality is made: Virality isn’t born, it’s made. Regardless of how plain or boring a product or idea may seem, there are ways to make it contagious. Just as recipes often call for sugar to make something sweet, we kept finding the same ingredients in ads that went viral, news articles that were shared, or products that received lots of word of mouth.

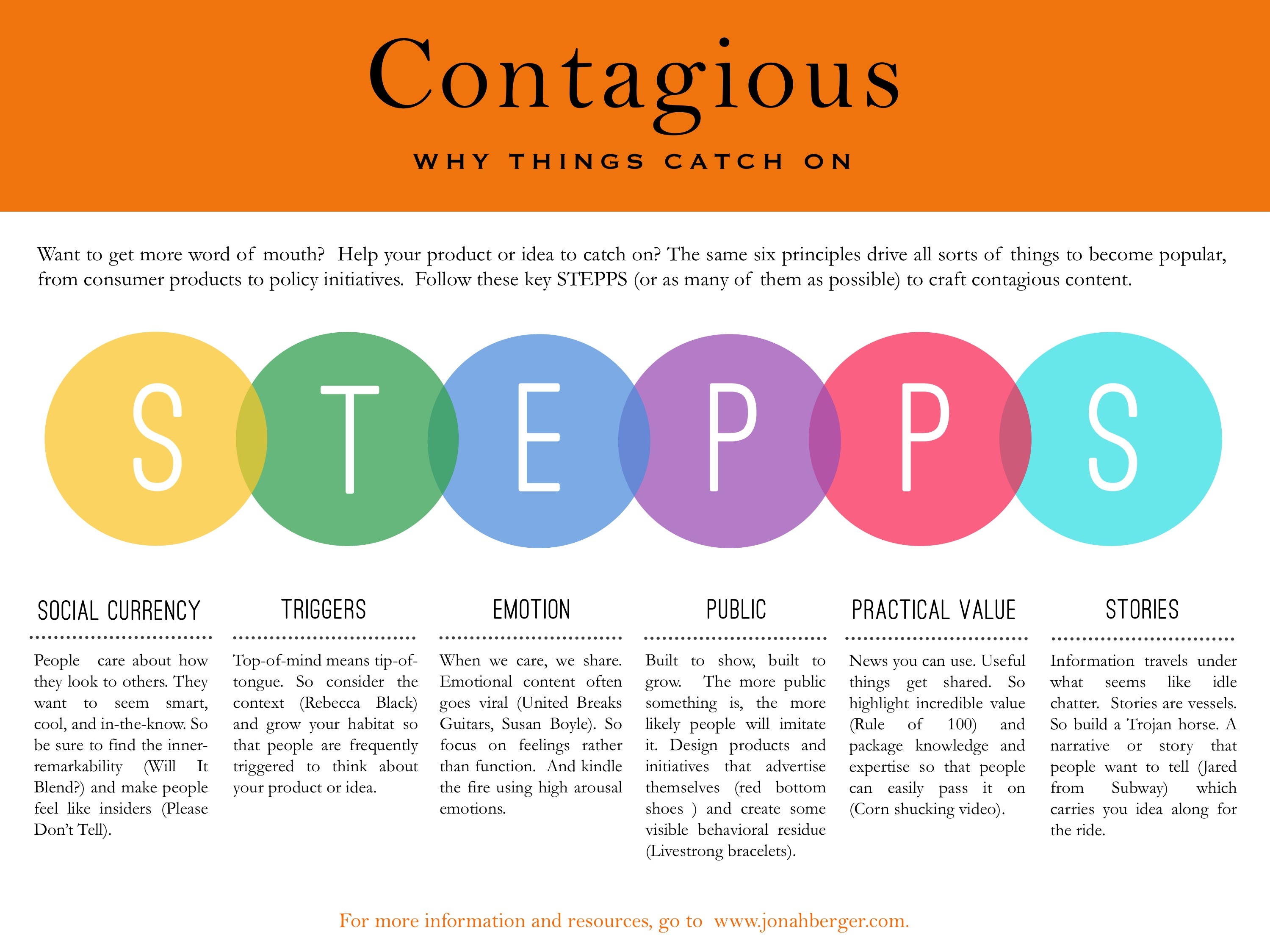

The six principles of contagiousness

These are the six principles of contagiousness: products or ideas that contain Social Currency and are Triggered, Emotional, Public, Practically Valuable, and wrapped into Stories.

Principle 1: Social Currency

How does it make people look to talk about a product or idea? Most people would rather look smart than dumb, rich than poor, and cool than geeky. Just like the clothes we wear and the cars we drive, what we talk about influences how others see us.

It’s social currency. Knowing about cool things—like a blender that can tear through an iPhone—makes people seem sharp and in the know. So to get people talking we need to craft messages that help them achieve these desired impressions.

We need to find our inner remarkability and make people feel like insiders. We need to leverage game mechanics to give people ways to achieve and provide visible symbols of status that they can show to others.

Principle 2: Triggers

How do we remind people to talk about our products and ideas? Triggers are stimuli that prompt people to think about related things. Peanut butter reminds us of jelly and the word “dog” reminds us of the word “cat.”

If you live in Philadelphia, seeing a cheesesteak might remind you of the hundred-dollar one at Barclay Prime. People often talk about whatever comes to mind, so the more often people think about a product or idea, the more it will be talked about.

We need to design products and ideas that are frequently triggered by the environment and create new triggers by linking our products and ideas to prevalent cues in that environment. Top of mind leads to tip of tongue.

Principle 3: Emotion

When we care, we share. Naturally contagious content usually evokes some sort of emotion. Some emotions increase sharing, while others actually decrease it. So we need to pick the right emotions to evoke. We need to kindle the fire. Sometimes even negative emotions may be useful.

Principle 4: Public

Can people see when others are using our product or engaging in our desired behavior? Making things more observable makes them easier to imitate, which makes them more likely to become popular.

So we need to make our products and ideas more public. We need to design products and initiatives that advertise themselves and create behavioral residue that sticks around even after people have bought the product or espoused the idea.

Principle 5: Practical Value

How can we craft content that seems useful? People like to help others, so if we can show them how our products or ideas will save time, improve health, or save money, they’ll spread the word. But given how inundated people are with information, we need to make our message stand out.

We need to understand what makes something seem like a particularly good deal. We need to highlight the incredible value of what we offer—monetarily and otherwise. And we need to package our knowledge and expertise so that people can easily pass it on.

Principle 6: Stories

What broader narrative can we wrap our idea in? People don’t just share information, they tell stories. We need to build our own Trojan horses, embedding our products and ideas in stories that people want to tell.

But we need to do more than just tell a great story. We need to make virality valuable. We need to make our message so integral to the narrative that people can’t tell the story without it.

STEPPS: Think of the principles as the six STEPPS to crafting contagious content. These

ingredients lead ideas to get talked about and succeed. Talking and sharing are some of our most fundamental behaviors. These actions connect us, shape us, and make us human.

Chapter 1: Social Currency

Social currency: If something is supposed to be secret, people might well be more likely to talk about it. The reason? Social currency. People share things that make them look good to others.

“Self-sharing” follows us throughout our lives. We tell friends about our new clothing purchases and show family members the op-ed piece we’re sending to the local newspaper. This desire to share our thoughts, opinions, and experiences is one reason social media and online social networks have become so popular.

Me-focus: Research finds that more than 40 percent of what people talk about is their personal experiences or personal relationships. Similarly, around half of tweets are “me” focused, covering what people are doing now or something that has happened to them. Why do people talk so much about their own attitudes and experiences?

It’s more than just vanity; we’re actually wired to find it pleasurable. Harvard neuroscientists Jason Mitchell and Diana Tamir found that disclosing information about the self is intrinsically rewarding. Sharing personal opinions activated the same brain circuits that respond to rewards like food and money.

Looking good: What people talk about also affects what others think of them. Telling a funny joke at a party makes people think we’re witty. So, not surprisingly, people prefer sharing things that make them seem entertaining rather than boring, clever rather than dumb, and hip rather than dull.

Word of mouth, then, is a prime tool for making a good impression—as potent as that new car or Prada handbag. Think of it as a kind of currency. Social currency. Just as people use money to buy products or services, they use social currency to achieve desired positive impressions among their families, friends, and colleagues.

Give people a way to make themselves look good while promoting their products and ideas along the way. There are three ways to do that:

(1) Find inner remarkability

(2) Leverage game mechanics

(3) Make people feel like insiders

Inner remarkability

Talking about remarkable things provides social currency.

Definition: Remarkable things are defined as unusual, extraordinary, or worthy of notice or attention. Something can be remarkable because it is novel, surprising, extreme, or just plain interesting. But the most important aspect of remarkable things is that they are worthy of remark.

Worthy of mention: Learning that a ball of glass will bounce higher than a ball of rubber is just so noteworthy that you have to mention it. Remarkable things provide social currency because they make the people who talk about them seem, well, more remarkable.

Social approval: Some people like to be the life of the party, but no one wants to be the death of it. We all want to be liked. The desire for social approval is a fundamental human motivation.

Interesting, surprising, or novel: The key to finding inner remarkability is to think about what makes something interesting, surprising, or novel.

Break pattern: One way to generate surprise is by breaking a pattern people have come to expect.

Universal: The best thing about remarkability, though, is that it can be applied to anything. You might think that a product, service, or idea would have to be inherently remarkable—that remarkability isn’t something you can impose from the outside.

Blendtec; But it’s possible to find the inner remarkability in any product or idea by thinking about what makes that thing stand out. Remember Blendtec, the blender company we talked about in the Introduction? By finding the product’s inner remarkability, the company was able to get millions of people to talk about a boring old blender.

Ex: black toilet paper in the bathroom.

Leverage game mechanisms

Game mechanics are the elements of a game, application, or program—including rules and feedback loops—that make them fun and compelling. You get points for doing well at solitaire, there are levels of Sudoku puzzles, and golf tournaments have leaderboards.

These elements tell players where they stand in the game and how well they are doing. Good game mechanics keep people engaged, motivated, and always wanting more. One way game mechanics motivate is internally. We all enjoy achieving things.

Discrete markers motivate us to work harder, especially when we get close to achieving them.

Game mechanics help generate social currency because doing well makes us look good. Game mechanics also motivate us on an interpersonal level by encouraging social comparison.

Compares: People don’t just care about how they are doing, they care about their

performance in relation to others.

Hierarchy: Just like many other animals, people care about hierarchy. Apes engage in status displays and dogs try to figure out who is the alpha. Humans are no different. We like feeling that we’re high status, top dog, or leader of the pack. But status is inherently relational. Being leader of the pack requires a pack, doing better than others.

Game mechanics boosts word of mouth. People are talking because they want to show off their achievements, but along the way they talk about the brands (Delta or Twitter)

Metrics: Leveraging game mechanics requires quantifying performance. Some domains like golf handicaps and SAT scores have built-in metrics. People can easily see how they are doing and compare themselves with others without needing any help. But if a product or idea doesn’t automatically do that, it needs to be “gamified.” Metrics need to be created or recorded that let people see where they stand.

Awards: Recipients of awards love boasting about them—it gives them the opportunity to tell

others how great they are. But along the way they have to mention who gave them the award.

Make people feel like insiders

Both used scarcity and exclusivity to make customers feel like insiders.

Scarcity is about how much of something is offered. Scarce things are less available because of high demand, limited production, or restrictions on the time or place you can acquire them.

Exclusivity is also about availability, but in a different way. Exclusive things are accessible only to people who meet particular criteria. But exclusivity isn’t just about money or celebrity. It’s also about knowledge. Knowing certain information or being connected to people who do.

Scarcity and exclusivity help products catch on by making them seem more

desirable. If something is difficult to obtain, people assume that it must be worth the effort. If something is unavailable or sold out, people often infer that lots of other people must like it, and so it must be pretty good.

Insiders: Scarcity and exclusivity boost word of mouth by making people feel like insiders. If people get something not everyone else has, it makes them feel special, unique, high status. And because of that they’ll not only like a product or service more, but tell others about it.

Paid shares: People are happy to talk about companies and products they like, and millions of people do it for free every day, without prompting. But as soon as you offer to pay people to refer other customers, any interest they had in doing it for free will disappear.

Customers’ decisions to share or not will no longer be based on how much they like a product or service. Instead, the quality and quantity of buzz will be proportional to the money they receive.

Chapter 2: Triggers

Fact: Every day, the average American engages in more than sixteen word-of-mouth episodes, separate conversations where they say something positive or negative about an organization, brand, product, or service.

Some word of mouth is immediate, while some is ongoing:

Immediate word of mouth: Is Imagine you’ve just gotten an e-mail about a new recycling initiative. Do you talk about it with your coworkers later that day? Mention it to your spouse that weekend? If so, you’re engaging in immediate word of mouth. This occurs when you pass on the details of an experience, or share new information you’ve acquired, soon after it occurs.

Ongoing word of mouth, in contrast, covers the conversations you have in the

weeks and months that follow. The movies you saw last month or a vacation you took last year.

Interesting products: As we suspected, interesting products received more immediate word of mouth than boring products. This reinforces what we talked about in the Social Currency chapter: interesting things are entertaining and reflect positively on the person talking about them. But interesting products did not sustain high levels of word-of-mouth activity over time. Interesting products didn’t get any more ongoing word of mouth than boring.

How triggers affect behavior

At any given moment, some thoughts are more top of mind, or accessible, than others. But stimuli in the surrounding environment can also determine which thoughts and ideas are top of mind.

Sights, smells, and sounds can trigger related thoughts and ideas, making them more top of mind. A hot day might trigger thoughts about climate change. Seeing a sandy beach in a travel magazine might trigger thoughts of Corona beer.

Indirect triggers: But triggers can also be indirect. Seeing a jar of peanut butter not only triggers us to think about peanut butter, it also makes us think about its frequent partner, jelly. Triggers are like little environmental reminders for related concepts and ideas.

Accessible thoughts and ideas lead to action.

Different locations contain different triggers: Churches are filled with religious imagery, which might remind people of church doctrine. Schools are filled with lockers, desks, and chalkboards, which might remind people of children or early educational experiences. And once these thoughts are triggered, they might change behavior

Ex: More than ten thousand more people voted in favor of the school funding initiative when the polling place was a school. Polling location had a dramatic impact on voting behavior

Top of mind means tip of tongue: Triggered products does not only get more immediate word of mouth, they also get more word of mouth on an ongoing basis. By acting as reminders, triggers not only get people talking, they keep them talking.

Top of mind means tip of tongue. So rather than just going for a catchy message, consider the context. Think about whether the message will be triggered by the everyday environments of the target audience.

Advertising triggers: Market research often focuses on consumers’ immediate reaction

to an advertising message or campaign. That might be valuable in situations where the consumer is immediately offered a chance to buy the product.

But in most cases, people hear an ad one day and then go to the store days or weeks later. If they’re not triggered to think about it, how will they remember that ad when they’re at the store?

Habitats: Biologists often talk about plants and animals as having habitats, natural

environments that contain all necessary elements for sustaining an organism’s life. Ducks need water and grasses to eat. Deer thrive in areas that contain open spaces for grazing.

Products and ideas also have habitats, or sets of triggers that cause people to think about them. Take hot dogs. Barbecues, summertime, baseball games, and even wiener dogs (dachshunds) are just a few of the triggers that make up the habitat for hot dogs.

Natural triggers: Most products or ideas have a number of natural triggers. Mars bars and Mars the planet are already naturally connected. But it’s also possible to grow an idea’s habitat by creating new links to stimuli in the environment.

What is an effective trigger?

Triggers can help products and ideas catch on, but some stimuli are better triggers than others.

Frequency of stimulus: One key factor is how frequently the stimulus occurs.

Frequency, however, must also be balanced with the strength of the link. The more things a given cue is associated with, the weaker any given association.

The color red, for example, is associated with many things: roses, love, Coca-Cola, and fast cars, to name just a few. As a result of being ubiquitous, it’s not a particularly strong trigger for any of these ideas.

Linking a product or idea with a stimulus that is already associated with many things isn’t as effective as forging a fresher, more original link. It is also important to pick triggers that happen near where the desired behavior is taking place.

Triggers and cues lead people to talk, choose, and use. Social currency gets people talking, but Triggers keep them talking. Top of mind means tip of tongue.

Chapter 3: Emotion

How viral happens: Few people have time to seek out the best content in this ocean of information. So they start by checking out what others have shared. As a result, most-shared lists have a powerful ability to shape public discourse.

For something to go viral, lots of people have to pass along the same piece of content at around the same time. Two reasons people might share things are that they are interesting and that they are useful.

The power of awe

According to psychologists Dacher Keltner and Jonathan Haidt, awe is the sense of wonder and amazement that occurs when someone is inspired by great knowledge, beauty, sublimity, or might.

It’s the experience of confronting something greater than yourself. Awe is a complex emotion and frequently involves a sense of surprise, unexpectedness, or mystery.

Experiment: awe boosted sharing.

Does any emotion boost sharing?

There are reasons to believe that experiencing any sort of emotion might encourage people to share. Talking to others often makes emotional experiences better. If we get promoted, telling others helps us celebrate. If we get fired, telling others helps us vent. Sharing emotions also helps us connect.

Say I watch a really awe-inspiring video, like Susan Boyle’s performance. If I share that video with a friend, he’s likely to feel similarly inspired. And the fact that we both feel the same way helps deepen our social connection.

It highlights our similarities and reminds us how much we have in common. Emotion sharing is thus a bit like social glue, maintaining and strengthening relationships. Even if we’re not in the same place, the fact that we both feel the same way bonds us together

The science of physiological arousal

Emotions can also be classified based on a second dimension. That of activation, or physiological arousal.

Arousal is a state of activation and readiness for action. The heart beats faster and blood pressure rises. Some emotions, like anger and anxiety, are high-arousal.

Opposite effect: When inspired by awe we can’t help wanting to tell people what

happened. Other emotions, however, have the opposite effect: they stifle action. Contentment deactivates. When people are content, they relax. Their heart rates slow, and their blood pressure decreases. They’re happy, but they don’t particularly feel like doing anything.

Funny content s shared because amusement is a high-arousal emotion.

Information is not enough: Marketing messages tend to focus on information.

But many times information is not enough. They need something more. And that is where emotion comes in. Rather than harping on features or facts, we need to focus on feelings; the underlying emotions that motivate people to action.

Experiment: Running doesn’t evoke emotion, but it is just as physiologically arousing. It gets your heart rate up, increases blood pressure, etc. So if arousal of any sort boosts sharing, then running in place should lead people to share things with others. Among students who had been instructed to jog, 75 percent shared the article—more than twice as many as the students who had been in the “relaxed” group. Thus any sort of arousal, whether from emotional or physical sources, and even arousal due to the situation itself (rather than content), can boost transmission.

One way to generate word of mouth is to find people when they are already fired up.

Chapter 4: Public

Making something more observable makes it easier to imitate. Thus a key factor in driving products to catch on is public visibility. If something is built to show, it’s built to grow.

The psychology of imitation

Whether making trivial choices like what brand of coffee to buy or important decisions like paying their taxes, people tend to conform to what others are doing. People imitate, in part, because others’ choices provide information.

So to help resolve our uncertainty, we often look to what other people are doing and follow that. We assume that if other people are doing something, it must be a good idea. They probably know something we don’t.

Psychologists call this idea social proof.

The power of observability

Behavior is public and thoughts are private: If most students were uncomfortable with the drinking culture, then why was it happening in the first place? Why were students drinking so much if they don’t actually like it? Because behavior is public and thoughts are private. Observability has a huge impact on whether products and ideas catch on.

Example: My colleagues Blake McShane, Eric Bradlow, and I tested this idea using data on 1.5 million car sales. Would a neighbor buying a new car be enough to get you to buy a new one? Sure enough, we found a pretty impressive effect. People who lived in, say, Denver, were more likely to buy a new car if other Denverites had bought new cars recently. And the effect was pretty big.

Approximately one out of every eight cars sold was because of social influence. Even more impressive was the role of observability in these effects. Cities vary in how easy it is to see what other people are driving. People in Los Angeles tend to commute by car, so they are more likely to see what others are driving than New Yorkers, who commute by subway. In sunny places like Miami, you can more easily see what the person next to you is driving than in rainy cities like Seattle.

By affecting observability, these conditions also determined the effect of social influence on auto purchases. People were more influenced by others’ purchases in places like Los Angeles and Miami, where it is easier to see what others were driving. Social influence was stronger when behavior was more observable.

Public visibility boosts word of mouth. The easier something is to see, the more people talk about it. Behavioral residue is the physical traces or remnants that most actions or behaviors leave in their wake. When publicly visible, these remnants facilitate imitation and provide chances for people to talk about related products or ideas.

Example: Clothing retailer Lululemon takes this idea one step further. Rather than make paper bags that are relatively durable, it makes shopping bags that are hard to throw away. Made of sturdy plastic like reusable grocery bags, these bags are clearly meant to be reused. So people use them to carry groceries or do other errands. But along the way this behavioral residue helps provide social proof for the brand.

Making the public private: Even in cases where most people are doing the right

thing, talking about the minority who are doing the wrong thing can encourage people to give in to temptation. Rather than making the private public, preventing a behavior requires the opposite: making the public private. Making others’ behavior less observable.

Chapter 5: Practical value

People like to pass along practical, useful information. News others can use. People don’t just value practical information, they share it. Offering practical value helps make things contagious.

Practical Value Vs Social Currency: If Social Currency is about information

senders and how sharing makes them look, Practical Value is mostly about the information receiver. It’s about saving people time or money, or helping them have good experiences. Sure, sharing useful things benefits the sharer as well. Helping others feels good. It even reflects positively on the sharer, providing a bit of Social Currency. But at its core, sharing practical value is about helping others.

The psychology of deal

Prospect theory: The way people actually make decisions often violates standard economic assumptions about how they should make decisions. Judgments and decisions are not always rational or optimal. Instead, they are based on psychological principles of how people perceive and process information. Just as perceptual processes influence whether we see a particular sweater as red or view an object on the horizon as far away, they also influence whether a price seems high or a deal seems good.

Reference point: People don’t evaluate things in absolute terms. They evaluate them relative to a comparison standard, or “reference point”. It might seem that old people are stingier than the rest of us. But there is a more fundamental reason that they think the prices are unfair. They have different reference points.

Diminishing sensitivity: Imagine you are looking to buy a new clock radio. At the store where you expect to buy it, you find that the price is $35. A clerk informs you that the same item is available at another branch of the same store for only $25. The store is a twenty-minute drive away and the clerk assures you that they have what you want there. What would you do?

Would you buy the clock radio at the first store or drive to the second store? If you’re like most people, you’re probably willing to go to the other store. After all, it’s only a short drive away and you save almost 30 percent on the radio. But consider a similar example. Imagine you are buying a new television. At the store where you expect to buy it, you find that the price is $650.

A clerk informs you that the same item is available at another branch of the same store for only $640. The store is a twenty-minute drive away and the clerk assures you that they have what you want there. What would you do in this situation? Would you be willing to drive twenty minutes to save $10 on the television? If you’re like most people, this time around you probably said no.

Diminishing sensitivity reflects the idea that the same change has a smaller impact the farther it is from the reference point.

Highlighting incredible value

Availability: As prospect theory illustrates, one key factor in highlighting incredible value is what people expect. Another factor that affects whether deals seem valuable is their availability. Somewhat counterintuitively, making promotions more restrictive can actually make them more effective.

Scarcity: Just like making a product scarce, the fact that a deal won’t be around forever makes people feel that it must be a really good one. Research finds that quantity purchase limits increase sales by more than 50 percent (for example “a maximum of 2 per customer”). The mere fact that not everyone can get access to this promotion makes it seem more valuable. This increases Practical Value, which in turn, boosts sharing.

Narrow audience: While broadly relevant content could be shared more, content that is obviously relevant to a narrow audience may actually be more viral.

Chapter 6: Stories

People think in narratives: People don’t think in terms of information. They think in terms of narratives. But while people focus on the story itself, information comes along for the ride.

Stories stick: Narratives are inherently more engrossing than basic facts. They have a beginning, middle, and end. If people get sucked in early, they’ll stay for the conclusion. When you hear people tell a good story you hang on every word.

Stories carry things. A lesson or moral. Information or a take-home message

Makes sense of the world: Stories are an important source of cultural learning

that help us make sense of the world.

Easy to remember: Stories provide a quick and easy way for people to acquire lots of knowledge in a vivid and engaging fashion. One good story about a mechanic who fixed the problem without charging is worth dozens of observations and years of trial and error. Stories save time and hassle and give people the information they need in a way that’s easy to remember.

Proof by analogy: You can think of stories as providing proof by analogy. First, it’s hard to disagree with a specific thing that happened to a specific person. Second, we’re so caught up in the drama of what happened to so-and-so that we don’t have the cognitive resources to disagree. We’re so engaged in following the narrative that we don’t have the energy to question what is being said. So in the end, we’re much more likely to be persuaded.

Making virality valuable

Brand integrated to the story: Virality is most valuable when the brand or

product benefit is integral to the story. When it’s woven so deeply into the narrative that people can’t tell the story without mentioning it.

Example – Panda says no: What makes these videos so great is not just that they’re

funny. The commercial would have been just as funny if the guy was dressed in a chicken suit or if the tagline was, “Never say no to Jim’s used cars.” They’re successful—and great examples of valuable virality—because the brand is an integral part of the stories.

Mentioning the panda is a natural part of the conversation. In fact, you’d have to try pretty hard not to mention the panda and still have the story make sense (much less get people to understand why it’s funny). So the best part of the story and the brand name are perfectly intertwined. That increases the chance not only that people telling the story will talk about Panda the brand, but also that they will remember what product the commercial is for, days or even weeks later. Panda is part and parcel of the story. It’s an essential part of the narrative.

Critical details in the narrative sticks: In trying to craft contagious content, valuable virality is critical. That means making the idea or desired benefit a key part of the narrative. It’s like the plot of a good detective story.

Some details are critical to the narrative and some are extraneous. Where were the different suspects at the time of the murder? Critical. What was the detective eating for dinner while he mulled over the details of the case? Not so important. Critical details stick around, while irrelevant ones drop out.

Study – Rumors: What happened to rumors as they spread from person to person? Did the stories stay the same as they were transmitted or did they change? And if they changed, were there predictable patterns in how rumors evolved?

They found that the amount of information shared dropped dramatically each time the rumor was shared. Around 70 percent of the story details were lost in the first five to six transmissions.

But the stories didn’t just become shorter: they were also sharpened around the main point or key details. Across dozens of transmission chains there were common patterns. Certain details were consistently left out and certain details were consistently retained.

Connect the content back to you: Make sure the information you want people to remember and transmit is critical to the narrative. Sure, you can make your narrative funny, surprising, or entertaining. But if people don’t connect the content back to you, it’s not going to help you very much.

Trojan horse: Build a Social Currency–laden, Triggered, Emotional, Public, Practically Valuable Trojan Horse, but don’t forget to hide your message inside. Make sure your desired information is so embedded into the plot that people can’t tell the story without it.